The Pipe Organ in China Project: Updates for June 2024

30 June 2024

Updates for June 2024:

The new organ for Christ Church, Shamian, Guangzhou, CAN2024, was installed during June. It is not clear when or if there will be a dedication of the instrument and/or a concert.

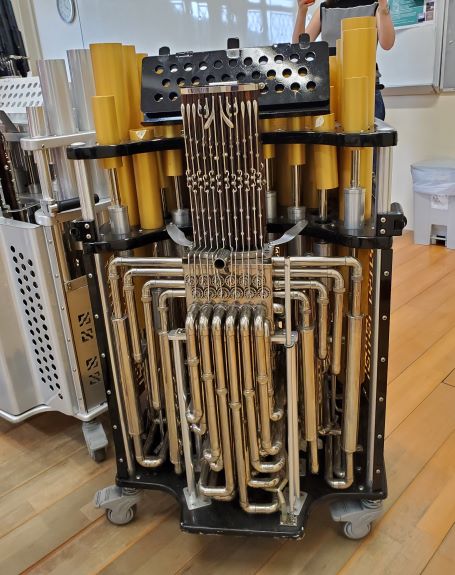

The Project is still waiting for an adequate photo of the organ in situ in Guangzhou. In the mean time, the new page for CAN2024 has a photo of the organ when it was still located in the Netherlands. The move of the organ from Europe to China was facilitated by Van den Heuvel Orgelbouw. Here is a photo, kindly sent to us by Emily Ke, of the organ under reinstallation:

Organs in the Census: 209

Hits this month: 1,211

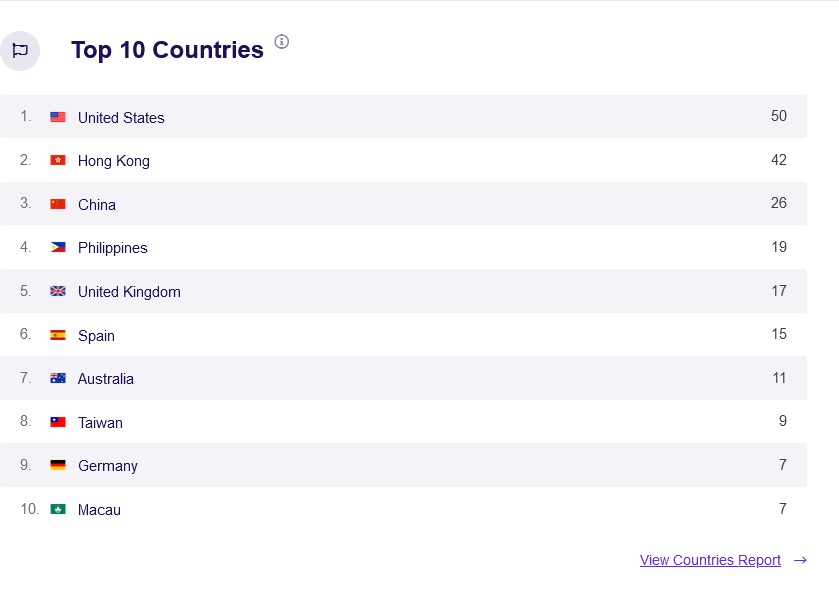

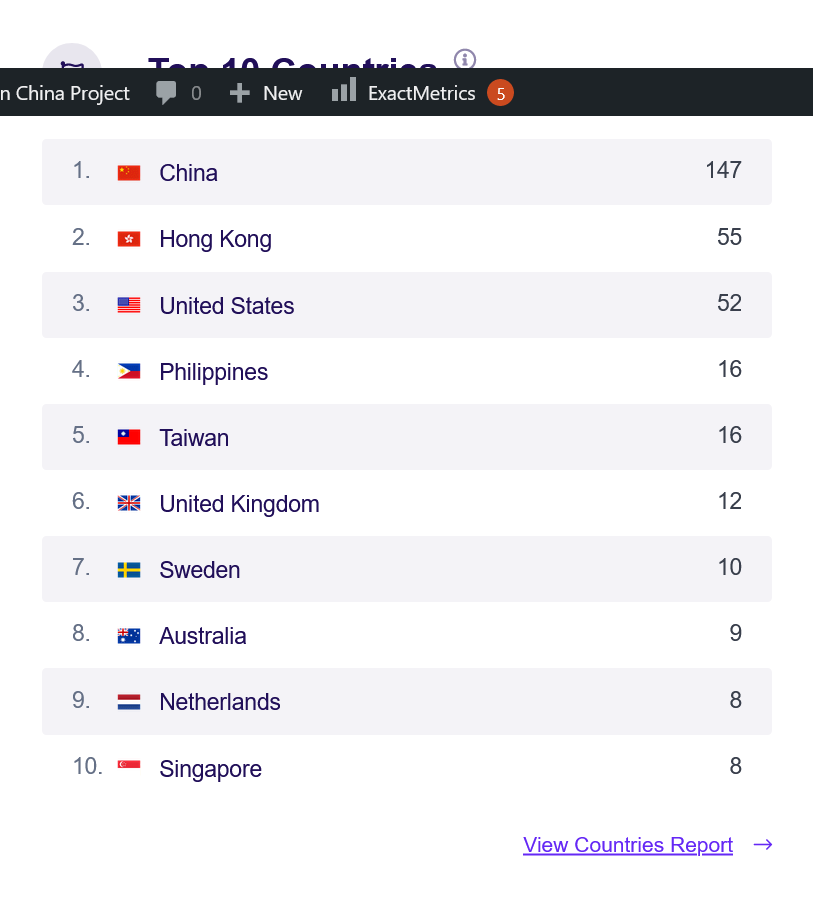

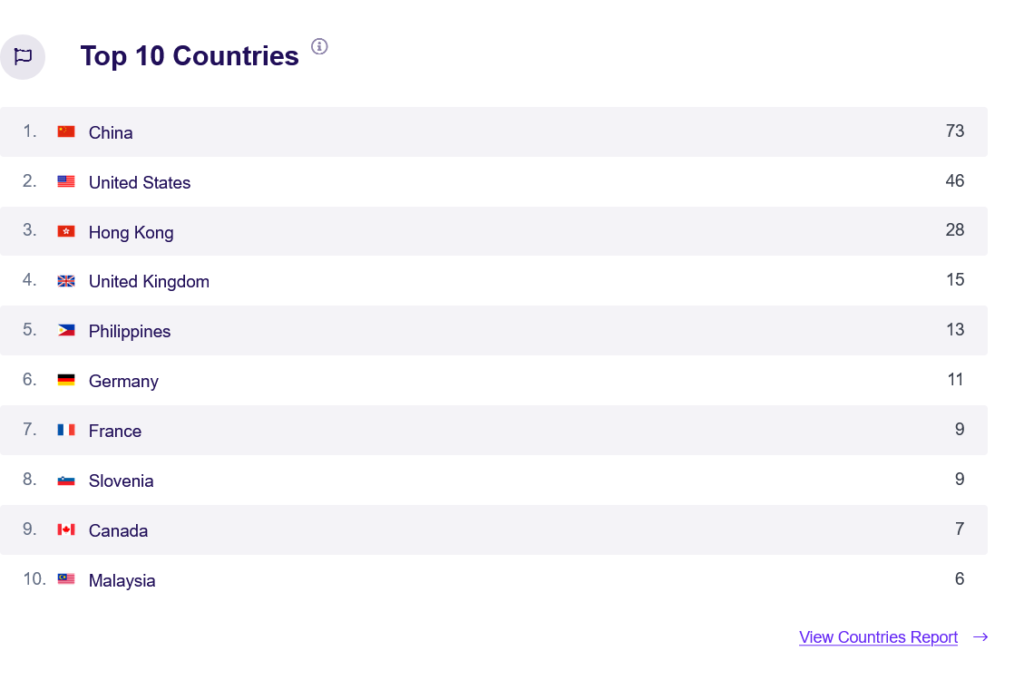

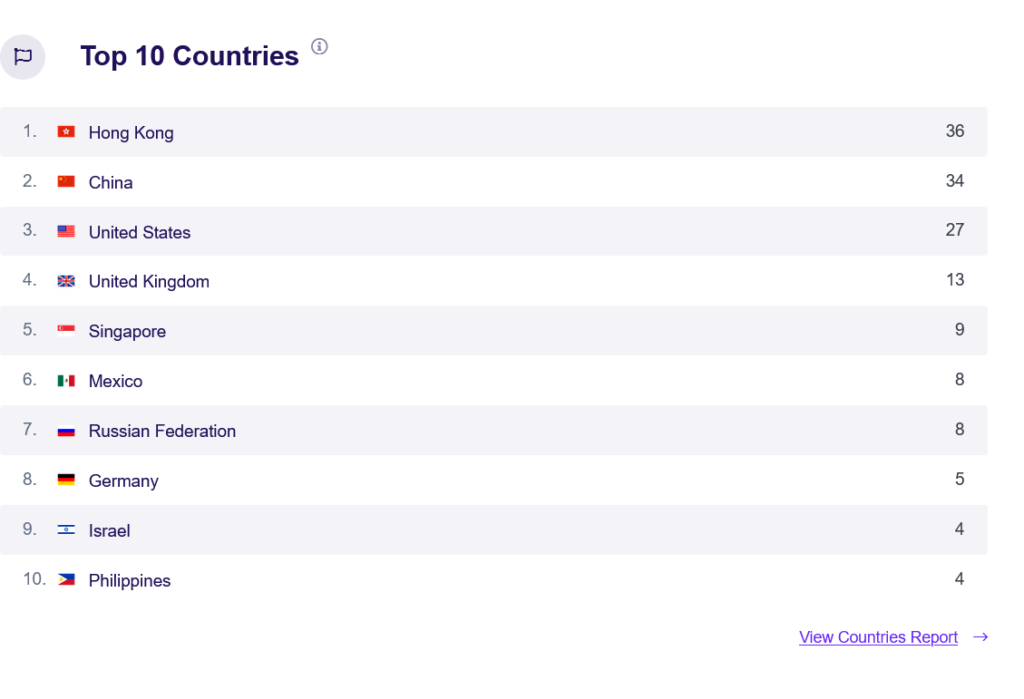

Top Ten Countries:

The Pipe Organ in China Project: Updates for May 2024

31 May 2024

There is only one update for May: we received some nice photos of HAR2015 from one of our friends, which have been put on the page for that installation.

During mid-May, the POCP Website was down for most of a week, due to migration of our host’s sites to new servers. We are sorry for any problems this may have caused our visitors. It caught us off guard as well, and was the source of some worry. Although everything is back to normal, it seems that in the process some pictures got resized downwards, and corrections will be made as we find them.

Organs in the Census: 208

Hits this month: 859

Top Ten Countries:

The Pipe Organ in China Project: Updates for April 2024

30 April 2024

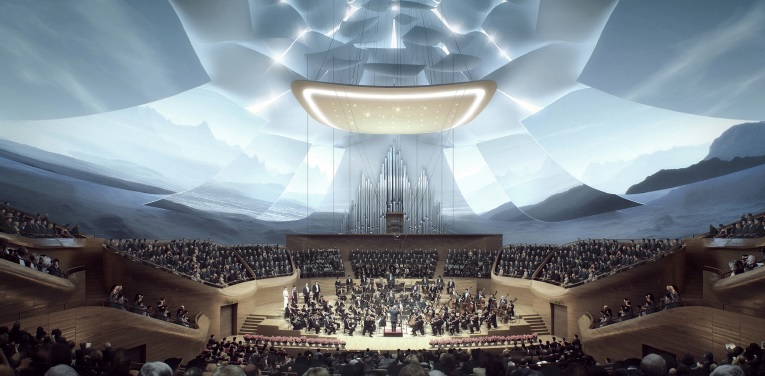

A new 4-manual and pedal Rieger organ with 86 stops, PEK2024, has been installed in the new ‘Beijing Performing Arts Center’, which is actually not in Bejing itself but in the city of Tongzhou, which now lies on the eastern side of a huge Beijing administrative district surrounding the Mainland Chinese capital. The Project assumes that this organ and the new hall were planned long prior to the COVID-19 epidemic, and that installation was delayed as a result. The Belgian firm, Kahle Acoustics, was a consultant on the project, and interesting details of their work on the hall can be found here: https://kahle.be/en/ref/beijingPerformingArtsCentreTongzhou.html

The pages for FCW1931 and FCW2005 have been updated. The Project thanks our correspondent, Emily Ke, for a photo we have used for the latter installation. The page for HKG2009 has also been updated, and the Project is grateful for new photos by organ builder, Cealwyn Tagle.

The Links page has also been updated.

Finally, clips from the Jesuita Cantat 2.0 concert, held in November 2023 as part of the 3rd Hong Kong Hymnos Festival, have now been uploaded to YouTube. Sung by Vox Antiqua, and conducted by Project founder Prof. David Francis Urrows, this program included Henry du Mont’s Messe royale du première Ton, sung in the form published and used in Shanghai by the Jesuits in the nineteenth century, and accompanied for the first time in 150 years by the ensemble formed by François Ravary SJ, of organ, dizi, and sheng.

Another major work, part of which was performed at Zikawei, was the Salut pour le jour du Saint Sacrement by Louis Lambillotte SJ, one of Fr. Ravary’s teachers. Again, this is probably the first time in at least a century since this work was last performed, at least publicly. Other works by Lambillotte, as well as compositions by Jules Dufour d’Astafort SJ, one of Lambillotte’s students and later his literary executor, and Saverio Mercadante, were also on the program.

The clips of these works from this concert, as well as music from the 2022 Jesuita Cantat 1.0 performance, can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/@voxantiquahk

Organs in the Census: 208

Hits this month: 1,116

Top Ten Countries for April 2024:

The Pipe Organ in China Project: Updates for March 2024

31 March 2024

The pages for PEK1989 and PEK2014 have been updated, as well as the FAQs.

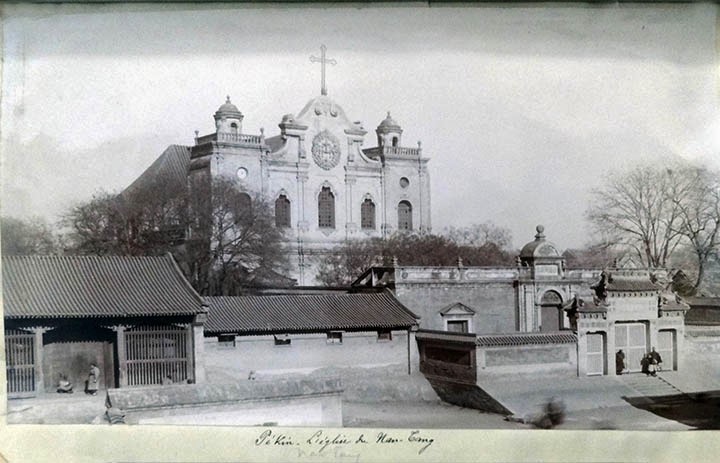

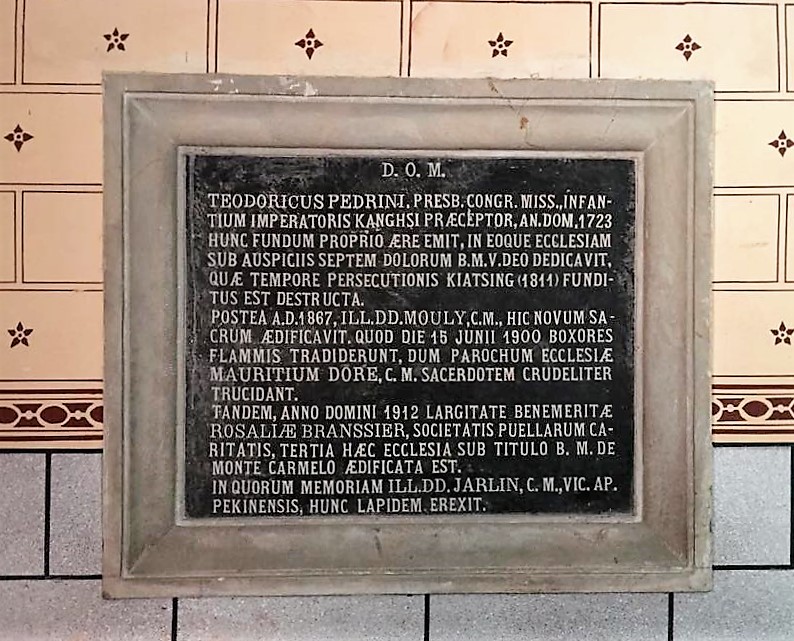

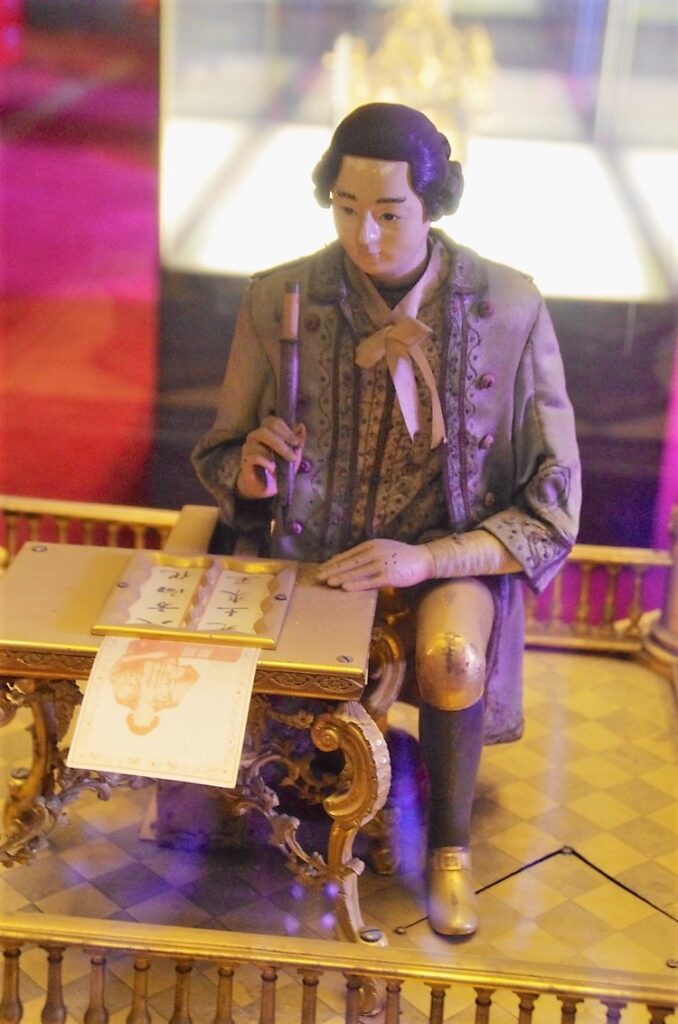

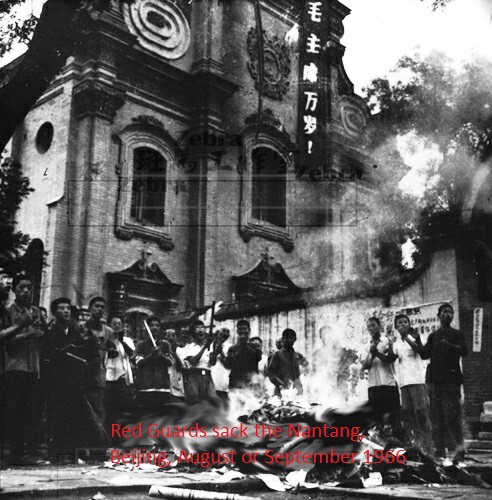

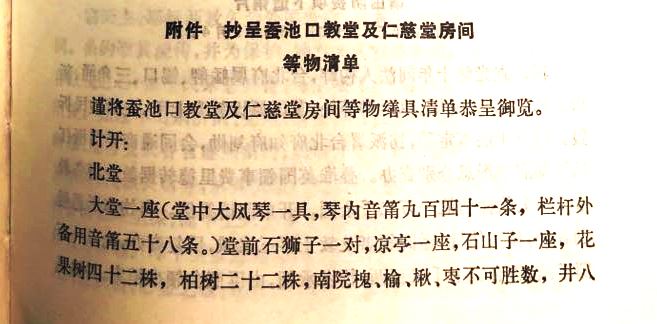

Word has reached The Project that PEK2015a, the Casavant organ in the Nantang in Beijing, is now under renovation by Carillon Technology Singapore (see photo below). The 1904 church (the Church of the Immaculate Conception) has been closed for most of the past nine years. On the heels of the dedication of the organ, it was shut after Christmas 2015 for no apparent reason. At some point it was reopened, and then closed again at the beginning of the COVID-19 epidemic. The entire interior of the church is being rebuilt/redecorated, as far as photographs seen by The Project appear to show.

On another topic, one of our correspondents has drawn The Project’s attention to an installation from the past ten years, where the builder has apparently removed the specs from their website. This is a concern to us, as we have relied on organ builders keeping this information on their webpages, and saving us the trouble of having to create a chart for these instruments (which would necessarily be less comprehensive.) We will follow this matter and try to replace the now-missing information where possible. To any of our visitors who finds that a link to a builder’s site no longer has the specs for the corresponding organ in the Census, we ask you to please let us know about this through an email to calcant@organcn.org

We wish all our visitors and friends a happy and blessed Easter Day.

Organs in the Census: 207

Hits this month: 900

PEK2015a in March 2024. Photo courtesy of Roster Wu/ Carillon Technology Singapore

The Pipe Organ in China Project: Updates for February 2024

29 February 2024

The FAQs have been updated, as well as the Errata list for Keys to the Kingdom.

The page for SHA1865 has been updated, with a new 1855 image of the Church of Our Savior, Hongkou, Shanghai.

Word has reached the Project of the upcoming (re-)installation of a 1964 II/7 Pels organ in Christ Church, Shamian, Guangzhou. The former Anglican church (now controlled by TSPM, and known as the shamian tang) is a historic building, completed around 1864 and replacing an earlier church destroyed by fire in 1856. The sale-and-relocation of the Pels organ has been facilitated by Van den Heuvel Orgelbouw, Dordrecht. This organ replaces CAN1904, a similarly-sized Walker organ which disappeared at some point after the late 1930s. Presently being packed for shipment, when the installation of the Pels organ is complete we will add it to the Census with all details. It is a positive sign to see another redundant organ installed in a church in Mainland China.

We wish all of our viewers and visitors a Happy Intercalary Day.

Organs in the Census: 207

Hits this month: 878

Top Ten Countries:

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for January 2024

31 January 2024

The only update for this month come from JL Weiler in Chicago, who sent us some photographs of their work on the restoration, along with Casavant, of PEK1920. We now have a nice picture of the newly-installed (though vintage) Kimball two-manual stopkey console (stopkey consoles were standard for theater organs, and take up slightly less space than drawknob consoles.)

Chinese Lunar New Year begins on the evening of 10 February. We wish all our friends and visitors a Happy Year of the Dragon.

–The Pipe Organ in China Project

Organs in the Census: 207

Hits this month: 862

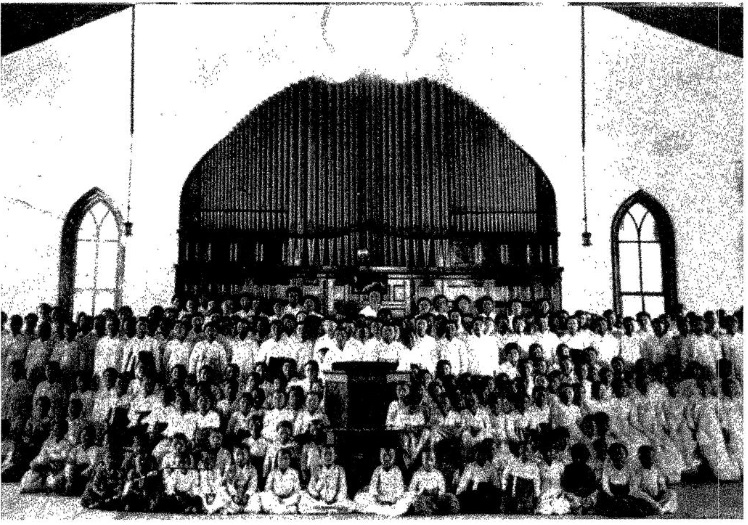

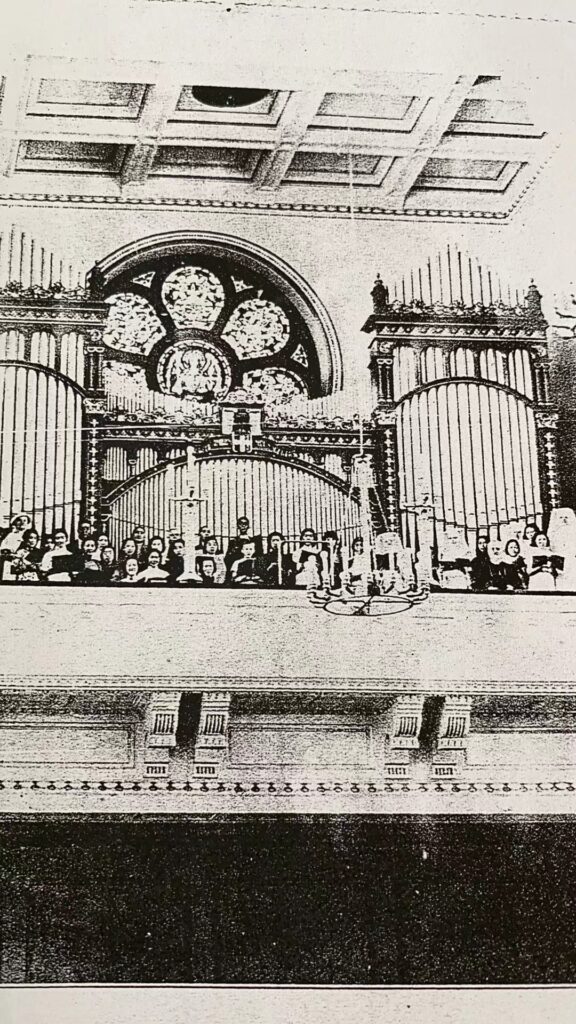

Photo of the Month: The I/7+Ped 1919 Hinners tracker action organ in Seoul, (now) South Korea, regrettably destroyed in the Korean War of 1950-53. (The photo is probably from The Diapason, 1 April 1919.) This is said to have been the first pipe organ installed in Korea.

Seoul, Korea, 1919 Hinners organ after installation.

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for December 2023

26 December 2023

A Happy Boxing Day to all of our visitors and friends.

A new two-manual chapel organ in Hong Kong, built by Diego Cera Organ Builders, has been installed in the historic Bishop’s House, and added to the Census: HKG2023.

The Project was informed on Christmas Day that PEK1920, the Kimball theater organ in the Auditorium of PUMC, has now been completely restored and reinstalled (with a new console) by Casavant and J.L. Weiler. It was re-dedicated in a concert held on 7 April 2023. Billed as a ‘Centennial Concert’, it in fact took place almost 102 years after the September 1921 dedication of the Auditorium and organ. Along with performances of various patriotic choral pieces by Chinese composers, organist Shen Yuan played the Toccata and Fugue in D minor (Bach), the Allegro, Chorale, and Fugue in D Major (Mendelssohn), Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 (Elgar), the Wagner and Mendelssohn wedding marches, and accompanied the ‘Ode to Joy’ (Beethoven). We have requested the specs of the rebuilt organ as well as new photos, and will update the page for this installation when we receive them.

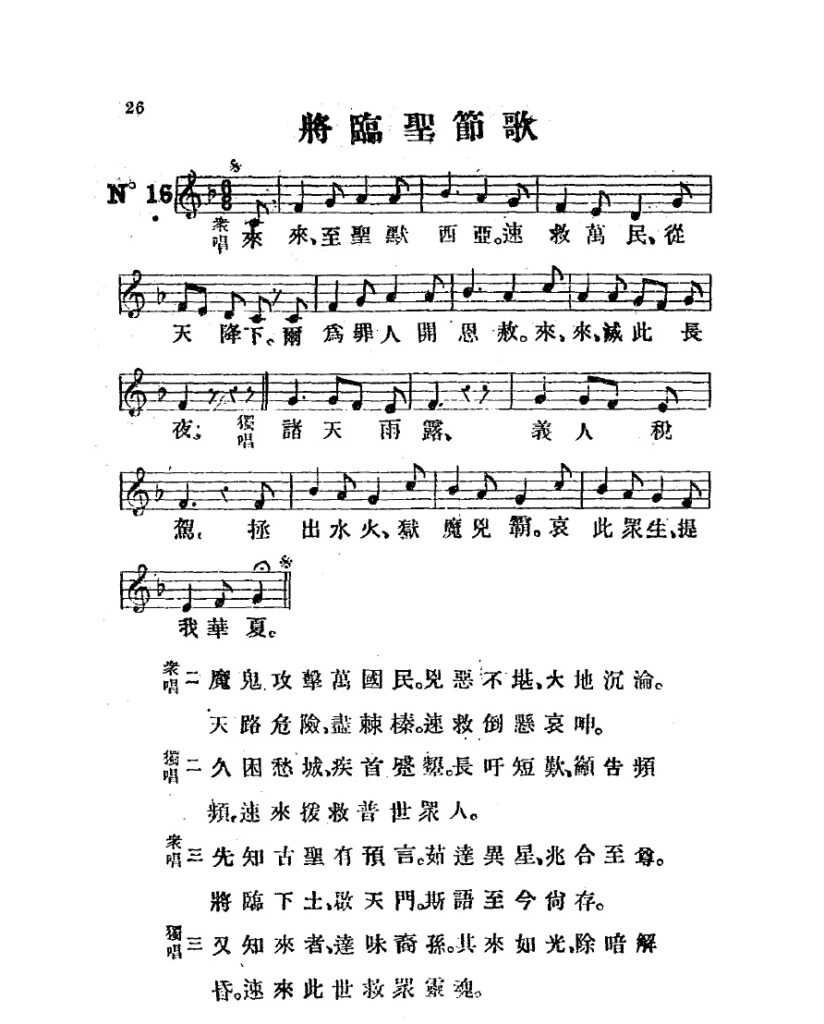

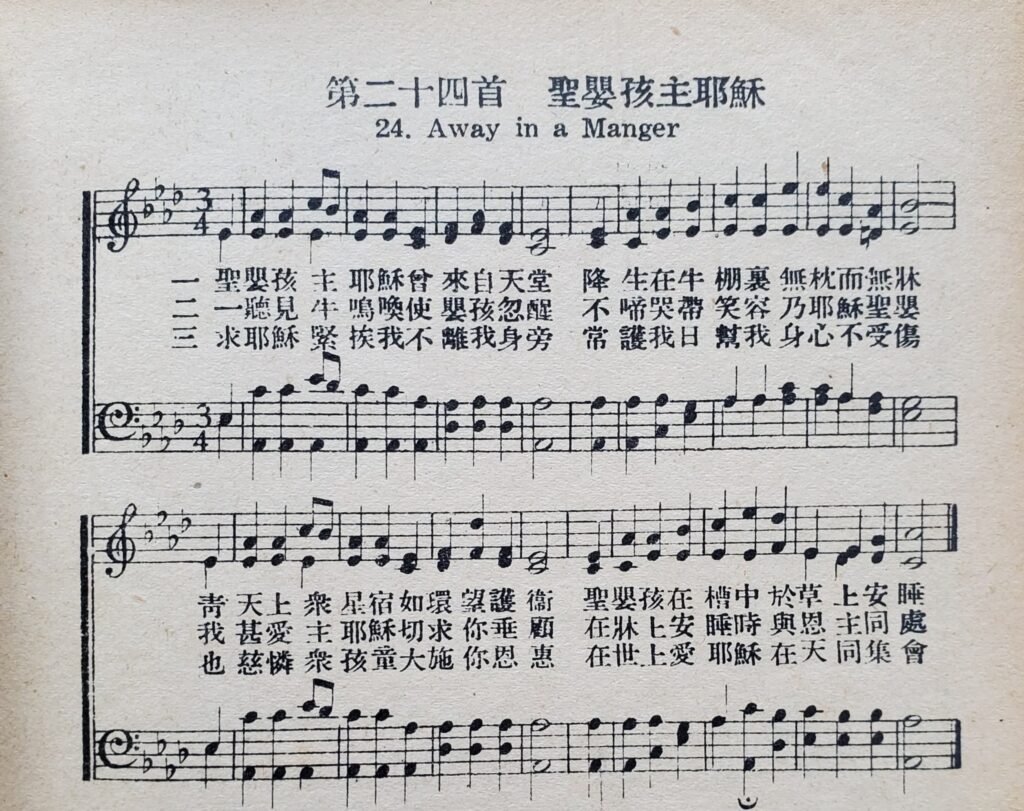

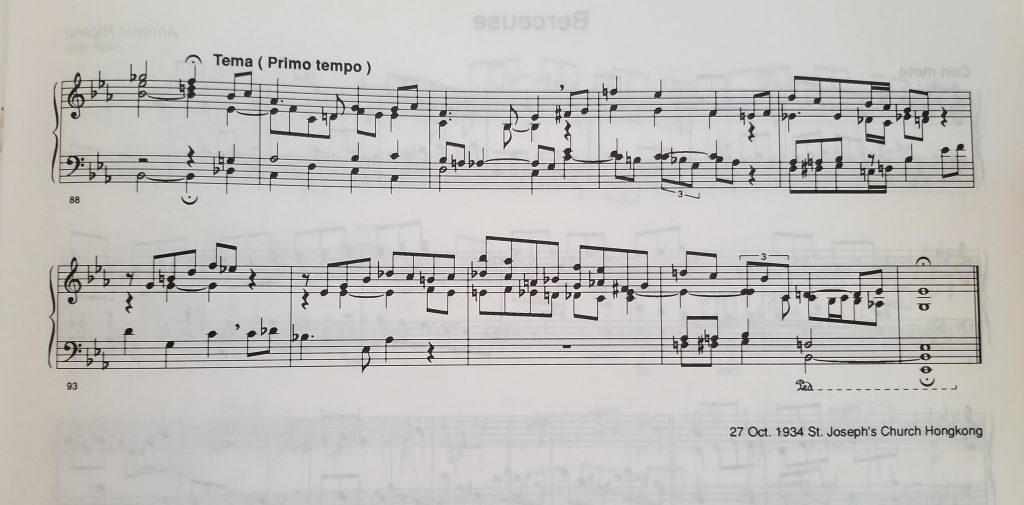

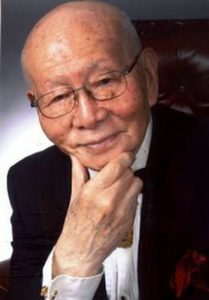

Prof. Urrows posted a blog entry in December on the 1969 Catholic Hymnal, published in Hong Kong. This hymnal includes a number of original liturgical works by Hong Kong composers of the time, including Father Antonio Riganti (1893-1965), who was discussed in a What’s New post in 2019. An interesting essay on his musical background by Father Riganti may be found here: https://musicasacra.org.hk/publish/composers/riganti_en.html

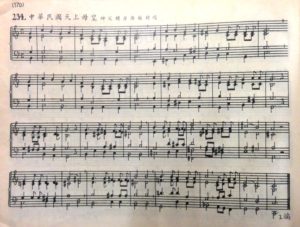

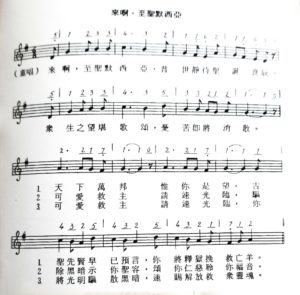

We wish all of our friends and visitors a Happy and Blessed Christmastide. Please enjoy singing the Chinese version of Venez, divin Messie, from the score below! This comes the 1926 SVD hymnal, Cantiques en Chinois, and this version is still sung in Roman Catholic churches in Mainland China to this day.

Organs in the Census: 206

A Catholic Hymnal from the 1960s, and more on Father Riganti.

19 December 2023

Prof. Urrows writes:

Over the years I have found a number of treasures in unlikely places in Hong Kong, but my favorite haunt is the Michaelmas Fair at St. John’s Cathedral at the end of October each year. This year, one of the things I picked up is a small hymnal, simply entitled Catholic Hymnal, and published in March 1969 by the Hong Kong Catholic Truth Society.

In the Foreword, we learn that this hymnal took seven years (1962-69) to complete. Since it is only 158 pages in a small format (13x19cm), one might wonder what took the Hong Kong Diocesan Hymnal Committee so long to finish its work. There appear to have been two reasons, both of which hit the Committee in 1965. The first of these was the end of the Second Ecumenical Council (known popularly as Vatican II), which sat from 1962 to 1965. This is noted with a dour comment about “liturgical changes introduced in recent years”, but that doesn’t begin to describe the earthquake of reforms that hit the Roman Catholic church worldwide in 1965, with those affecting music satirized in Tom Lehrer’s classic comedy song, The Vatican Rag. Obviously, in 1965 the Committee had to some extent to begin all over again with a new set of (confusing) directives.

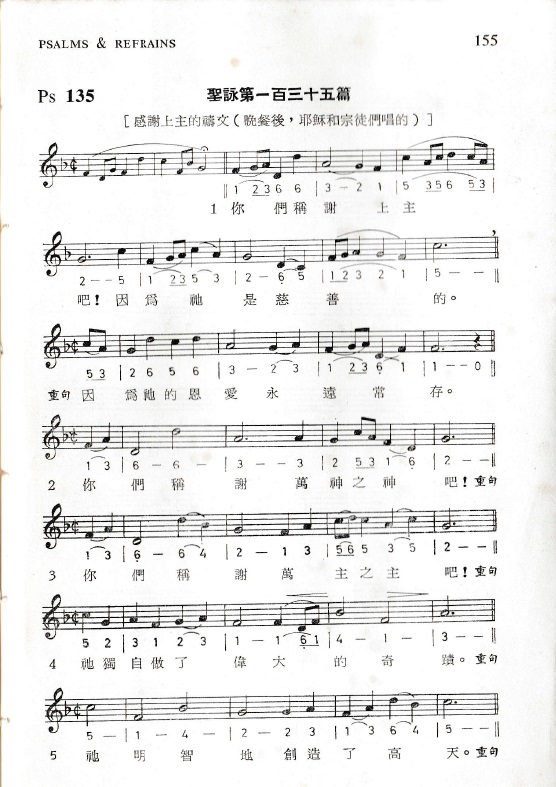

The second reason was the death of P. Antonio Riganti PIME (1893-1965) in the same year. Father Riganti has appeared in What’s New before (for July 2019), and he was the first Chairman of this hymnal’s Committee. I found in this hymnal two hymns composed by Father Riganti, as well as two ‘Psalm Refrains’ (what we would today call Responsorial Psalms) for Psalms 2 and 21, as well as five complete Psalms settings (22, 99, 116, 129, and 135). All of these are given with words and melody only. If there was an accompaniment edition, I have not seen it.

Father Riganti’s hymns are through-composed, and not verse-hymns. The first, Now in the week’s new dawn, is an entrance hymn in English with a traditional four-square feel, but also a fluid sense of melody. The words seem to be by one of Riganti’s committee colleagues, a Sister Maria Eucharistica. The second hymn in in Chinese, Lead the Holy Church. This is written in a hexatonic scale (no leading tone) and is printed with Western music notation and Chinese jianpu numerical notation. This is also the approach Riganti took with the responsorials, and the five complete Psalms (see Psalm 135 (=Psalm 136 in most psalters) below).

We see several different demands being catered to here. First, the emphasis on local-language worship. The second, is the approximation of melody using scales other than the European major/minor tradition (there are quite a few well-known hymns included, with both English and Chinese words.) Third, increasing congregational participation in singing. And finally, this hymnal reflects a period of transition in the Catholic church worldwide, as it tried to digest the directives of Vatican II. When it came to music, these directives were widely misrepresented and misunderstood. The Hong Kong 1969 Catholic Hymnal does better than many others from this period in balancing new and old, in my opinion. And I think much of this success must be due to the three years during which Father Riganti led the committee.

Earlier this year, a descendant of Father Riganti, who still lives in Italy, contacted The Project. We replied, with a request for more information about him, but to date we have unfortunately heard nothing back.

Psalm 135 (136), setting by Father Antonio Riganti.

The Pipe Organ in China Project: Updates for November 2023

30 November 2023

With the disastrous effects of China’s ‘Zero-Covid Policy’ subsiding in some ways, long-delayed installations are finally taking place. But this month we have added a new organ to the Census with a different origin. This is a two-rank positive made at the Dalian University of Technology by Prof. Wang Xiaohu and his graduate students between 2021 and 2023. Prof. Hu’s goal is to stimulate pipe organ building locally in China. This means that DRN2023 is the first pipe organ built entirely in Mainland China, Hong Kong, or Macau since the closure of the firms of W.C. Blackett (Hong Kong), and Moutrie and Sam Lazaro (Shanghai) at the start of the Sino-Japanese War around 1939. The Project will follow with interest these developments.

Pages for TJN1913, DRN1914, and SHA1925 have been updated.

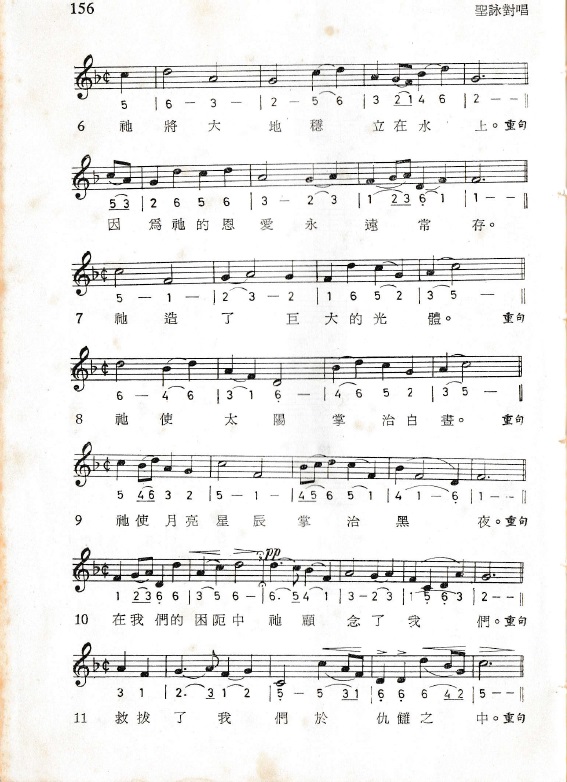

The Hong Kong Chapter of the American Guild of Organists held their annual member’s recital on 24 November. The program featured music by Albright, Bach, Boëllmann, Bolcom, Langlais, Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, and Vierne. The program is shown below.

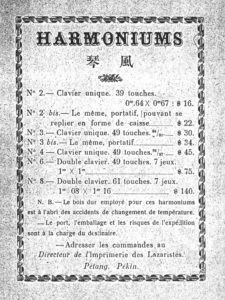

Prof. Urrows contributed a blog post in November on the mystery of a harmonium that used to be in the Chapel of St. Joseph in Ma On Shan Village. Any communications about the whereabouts of this instrument will be gratefully received at calcant@organcn.org.

And the fourth annual Hymnos Festival is taking place in Hong Kong and Macau as this update is posted. On 25 November, the second Jesuita Cantat (Jesuita Cantat 2.0) concert took place in Hong Kong, presenting more music from the mid-19th Century French Roman Catholic missions in Shanghai. It was held at the little-known (but enormous) Chapel of Christ the King in Causeway Bay, with its superb 3.5 second reverberation time, ideal for choral music.

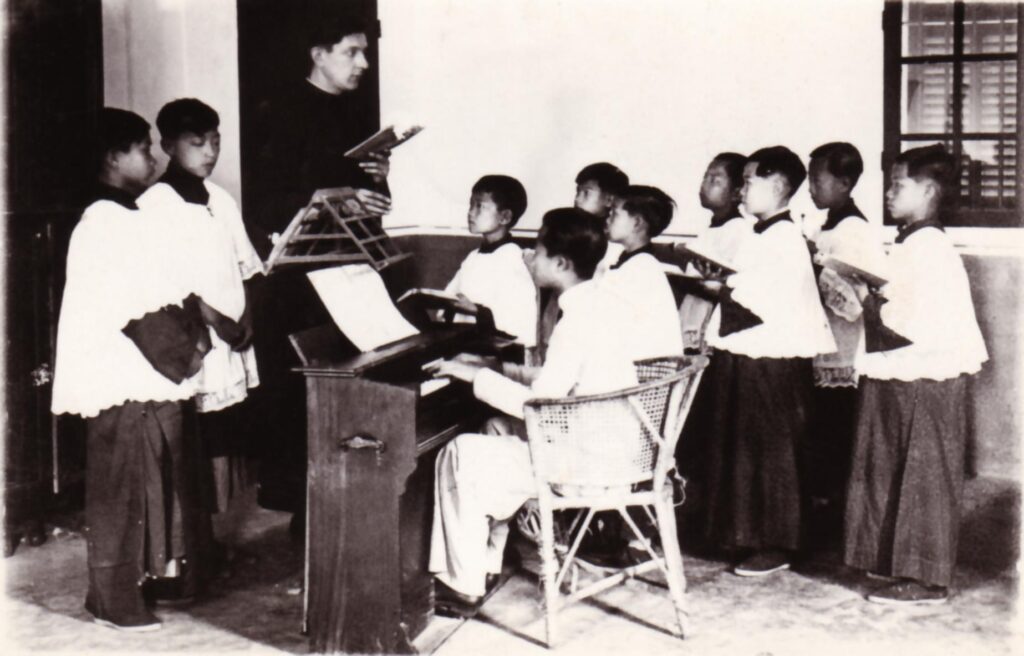

Prof. Urrows and Andrew Leung conducted the choir, Vox Antiqua, with guest players from Good Hope School on dizi (transverse flute), and sheng (bamboo mouth organ), Karen Yeung, dulzian, Chere Ko, organ, and guest singers Rachel Kwok, soprano, and Samantha Chong, mezzo-soprano. The major works were the Salut pour le jour du St. Sacrement of Louis Lambillotte, of which the last movement was sung in Shanghai under the direction of Fr. François Ravary, and the Messe royale du premier Ton of Henry du Mont, which was the standard setting of the Ordinary in the China missions until the 1920s. This was the first time that Father Ravary’s liturgical ensemble of organ, dizi, and sheng– a hidden ‘soundworld’ –had been recreated in 150 years (photo below). Other works known to have been sung in Shanghai (by Lambillotte, Jules Dufour SJ, Saverio Mercadante, and a Marian hymn sung to the melody of the French folksong, Des concert avec les anges), were also on the program. When clips from this concert of music from ‘China’s Hidden Century’ are available, we will post the links.

Organs in the Census: 205

Hits this month: 1,176

Prof. Urrows conducts a rehearsal of du Mont’s Missa Regia at the Chapel of Christ the King, Hong Kong.

What happened to the Ma On Shan Harmonium?

5 November 2023

Prof. Urrows writes:

One of the small, nagging mysteries that I have dealt with during my many years in Hong Kong is the question of what became of a harmonium that used to be in the Chapel of St. Joseph in Ma On Shan Village (馬鞍山村)? The Project usually doesn’t concern itself with harmoniums, but a derelict harmonium in a nearby derelict church invites investigation.

The chapel is an early 20th Century building, perched on a hill overlooking the former tiny mining community in the hills of Ma On Shan (Horse Saddle Hill) on the east side of the Shing Mun River. The mining industry collapsed after the Second World War due to exhaustion of the ore in the hills. With the development in the 1980s of Ma On Shan New Town, the later Chapel of St. Francis near the river was eventually rebuilt in a more central location as a new parish church to serve the local population. The Chapel of St. Joseph was formally closed in 1999, but the church remained accessible for some years, perhaps until about 2013. https://www.stfrancis.org.hk/en/patron-history/

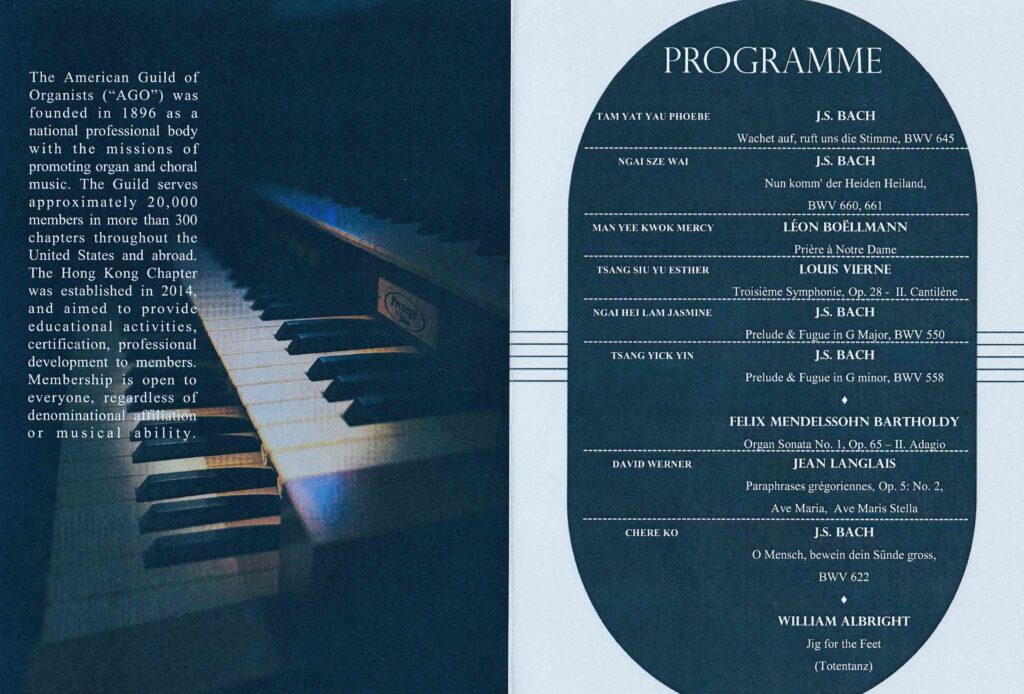

I happen to know this, because two magazine articles published between the mid-2000s and about 2012 contained photos of the harmonium in the tiny organ loft of the chapel. The first was a Hallowe’en-themed fashion spread (“Princesses of Darkness”) that appeared the Sunday Morning Post Magazine around 2007.

The second photo appeared in the Chinese-language magazine, Weekend Weekly (新假期) around 2012, in a things-to-do piece about Ma On Shan Village. The church was still clearly open to visitors at that time.

By 2014, when I managed to get up to the village, the church was closed, and several heavy padlocks secured the gate. Attempts to call a phone number on a small sign there failed to reach anyone.

But: what happened to the harmonium? And can anyone recognize the builder/catalog type? Except for the missing stop plates, it doesn’t look to have been in such bad condition. All info gratefully received at calcant@organcn.org

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for October 2023

1 November 2023

Everything, Everywhere, All at Once. There are many things for The Project to report after a quiet summer.

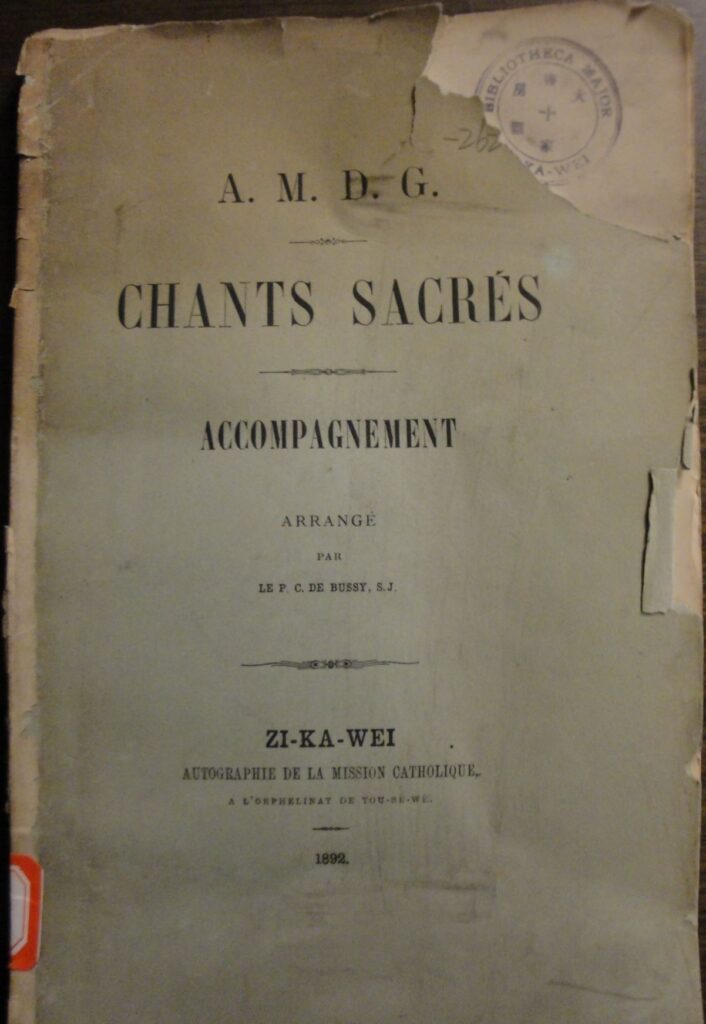

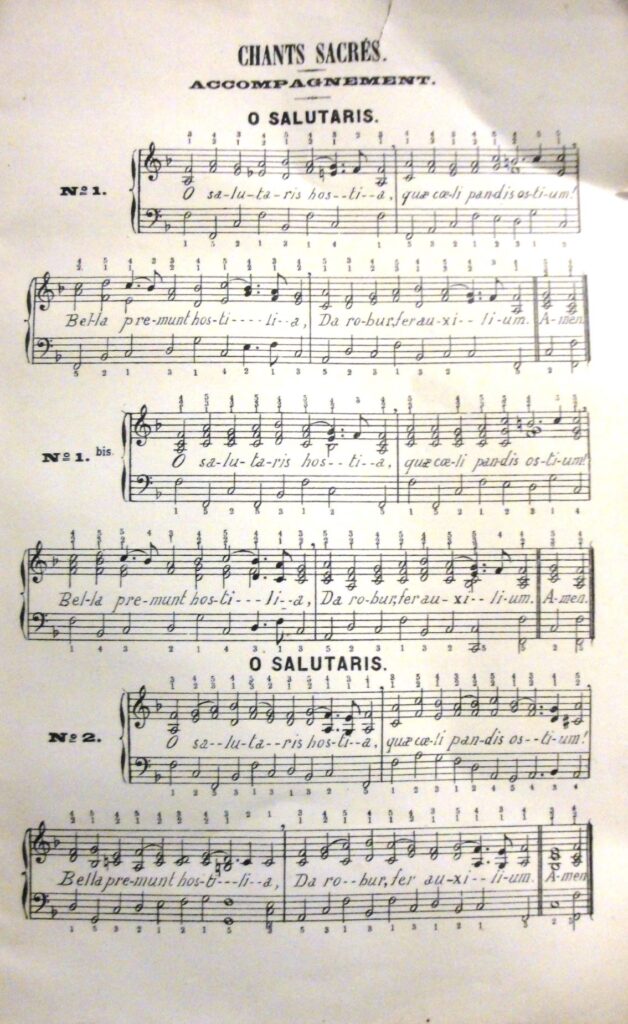

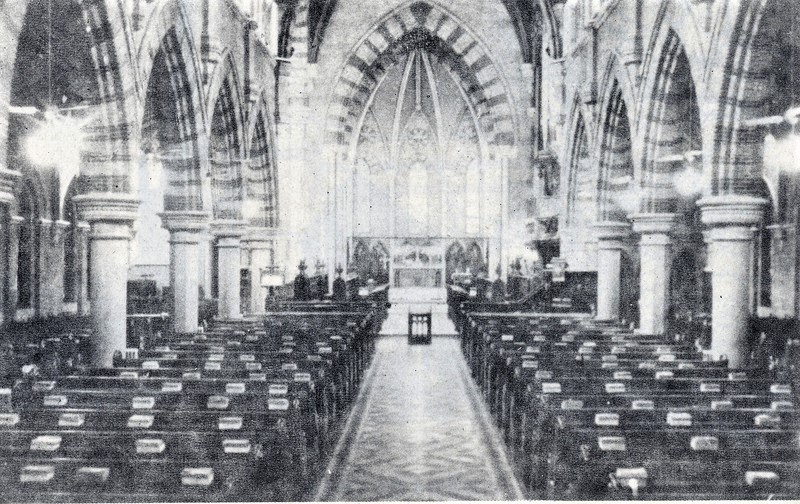

The main event has been the long-awaited dedication of SHA2023, a three-manual and pedal 34-stop organ in the Cathedral of St. Ignatius Loyola at Zikawei (Xujiahui) in Shanghai. Built by Diego Cera Organ Builders, the installation was planned for 2020; COVID got in the way, leading to over 3 years of delays.

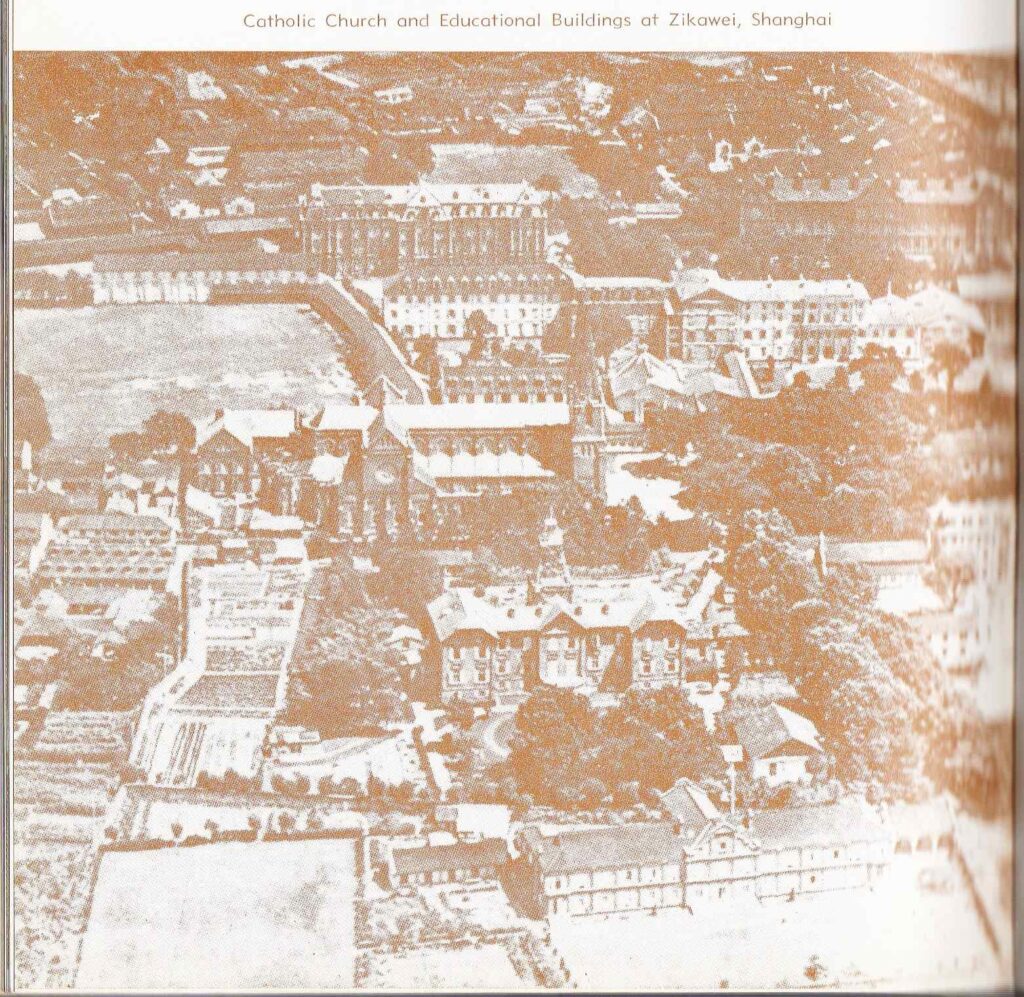

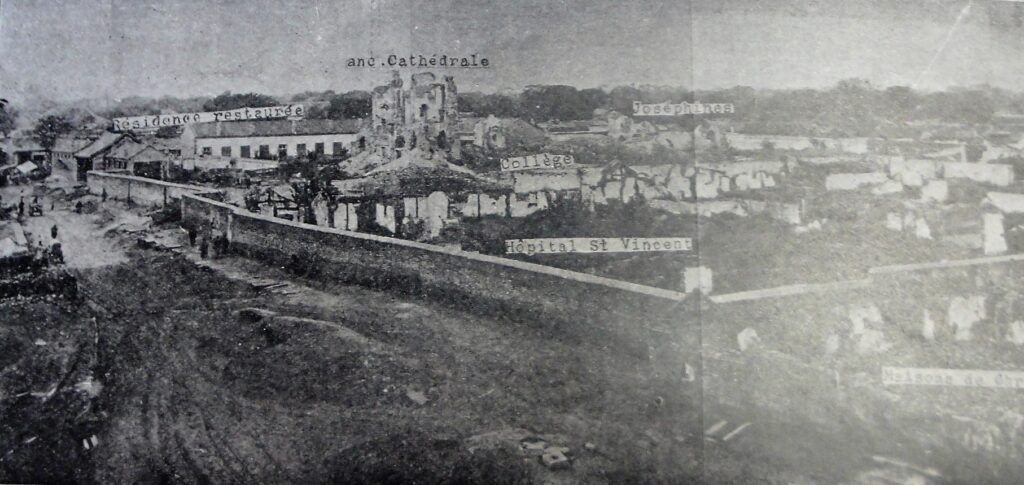

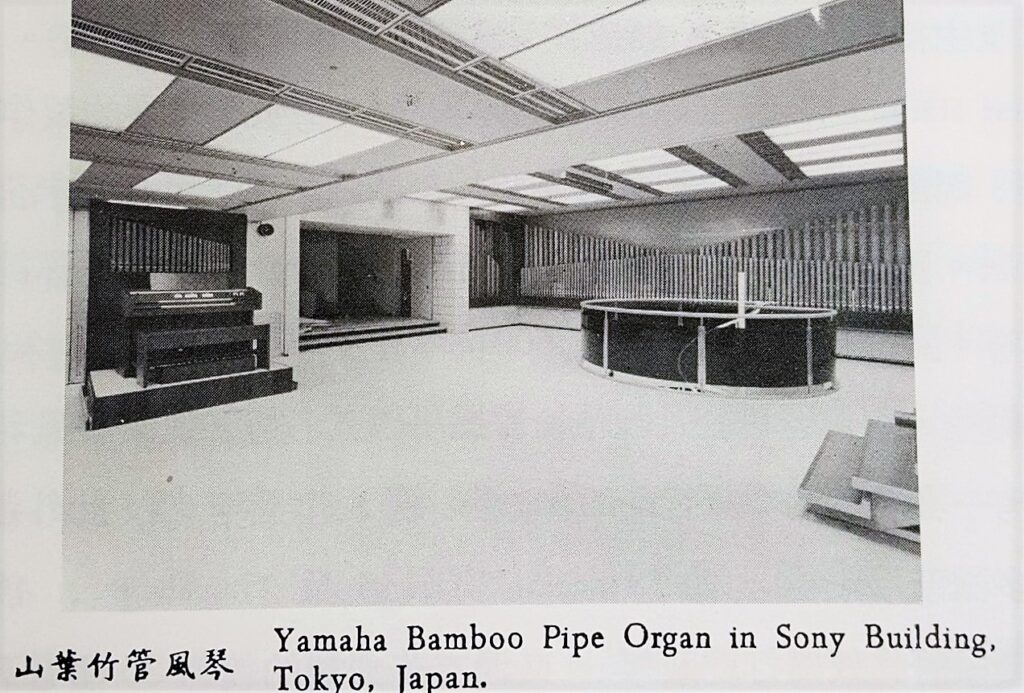

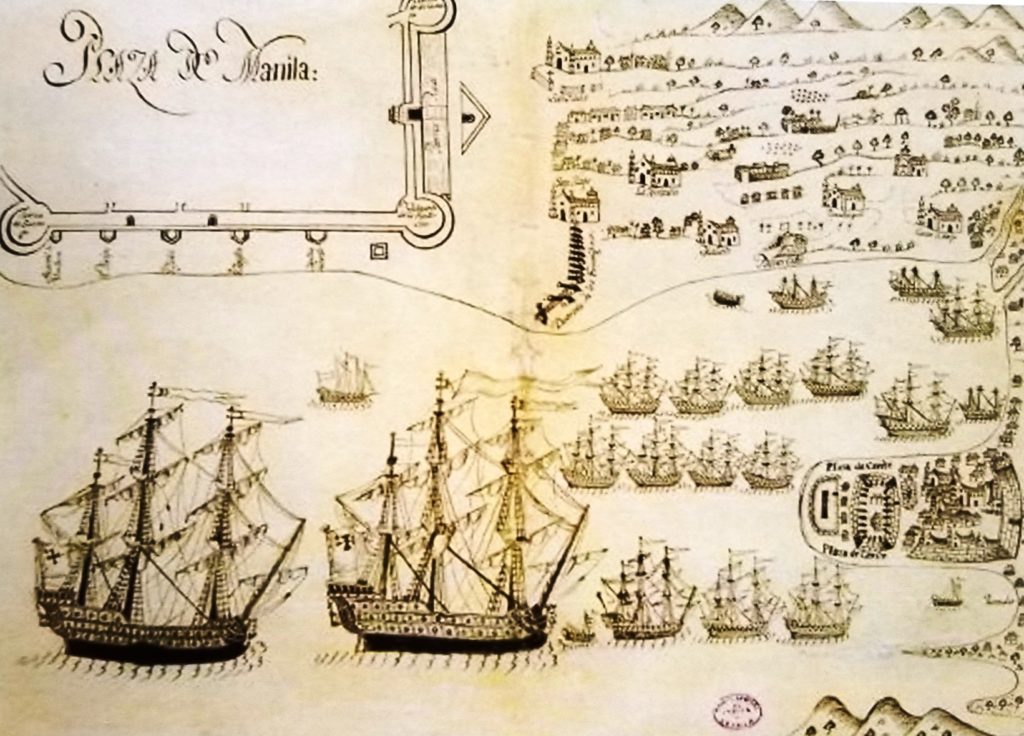

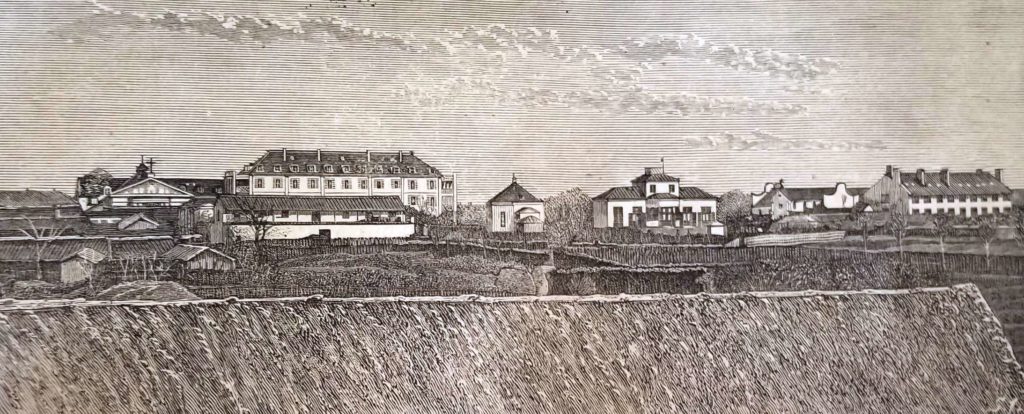

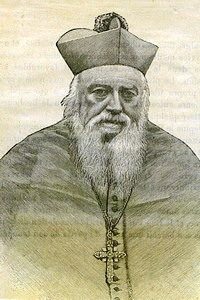

This new organ is closely related to the origins of The Project. The cathedral church itself is the 1910 successor to the first Church of St. Ignatius built in 1847. For this earlier church, Léopold Deleuze and François Ravary eventually built a bamboo organ (SHA1859), their third instrument after the groundbreaking organ for St. Francis Xavier (SHA1857), and the three-rank positive for the son of Napoléon III (SHA1858). In fact, one of the interesting discoveries of the past year has been that the 1847 church survived the Second World War, and may have still stood until the 1960s. The photo (below, looking north), taken from Fr. Thomas F. Ryan’s 1942 book, China Through Catholic Eyes, is an aerial view from the 1930s. The old church, with its Chinese-style lantern, is seen just slightly to the northeast of the 1910 Neo-Gothic Cathedral.

As a result of information shared with The Project by the Tushanwan Museum (which is functioning as a museum for the whole of the Zikawei Jesuit ‘village’), the page for SHA1883 (which was moved to the 1910 cathedral in 1925) has been updated significantly, with new photos, for which The Project is grateful.

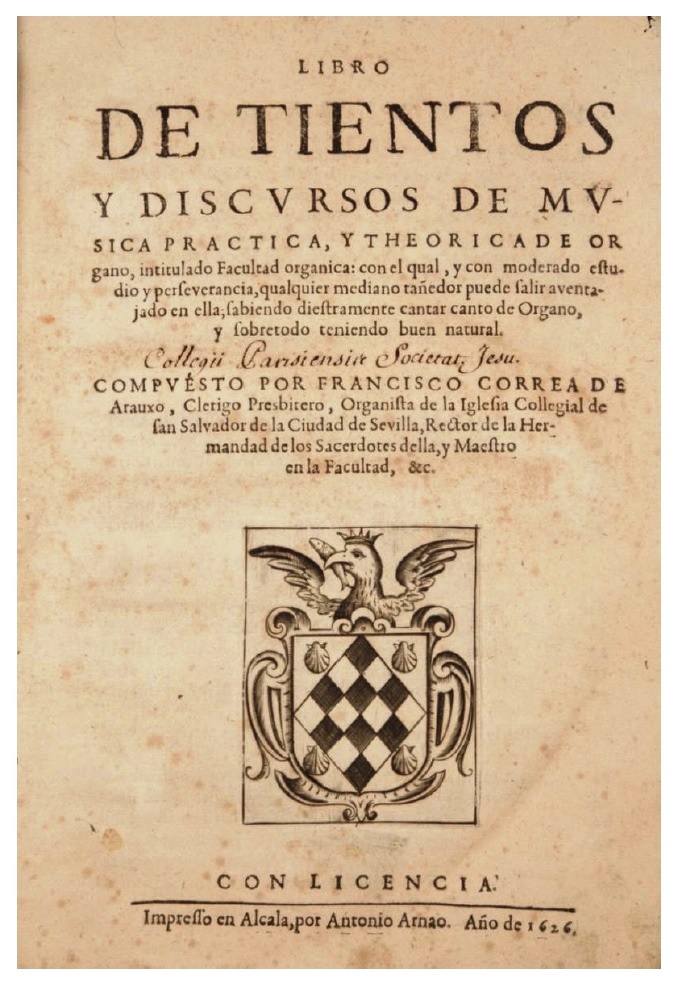

The Links page has also been updated with corrected and added links, in particular www.formosaorganist.com, a Chinese-language website relating to organ performances and audience development in Taiwan. Prof. Urrows was a guest of Fu Jen Catholic University in Taipei in early October, and gave a lecture on “François Ravary SJ: Missionario musicista in China’s ‘Hidden Century’” on 3 October.

The pages for PEK2003 and TAO2008 have also been updated.

Aerial view of Zikawei, 1930s.

Organs in the Census: 204

Hits this month: 964

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for September 2023

30 September 2023

The new Diego Cera Organ Builders III/34 installation at the Cathedral of St. Ignatius Loyola at Zikawei (Xujiahui) in Shanghai has now been completed. A dedication was held on Sunday, 24 September, with Philippine organist Alejandro Consolacion II playing the instrument for the service. This is the first installation of an organ in the cathedral in 98 years. The Project is waiting for photos of the organ and details of the event. An entry in the Census for this instrument will be made sometime in October, however we have updated the number of organs in the Census to 204.

At the same time, The Project has learned that the installation of the long-awaited Casavant organ for the Cathedral in Macau has been postponed yet again. The tentative date for start of the work now seems to be in 2024.

And while The Project does not really cover the area of organ repertory in China, The American Organist issue for September 2023 included an interesting article on four women composer/organists, now living in the US and Canada, of Chinese descent and their works (Calvert Johnson, “Organ Works by Women of Chinese Ancestry”, TAO, Vol. 57/9, pp. 48-59.) They are: Wang An-Ming (b. Shanghai, 1926), also known as Marion Wang Mak; Hope Lee (b. Taiwan, 1953); Vicky Chang Pei-lun (b. Taiwan, 1966); and Chelsea Chen (b. San Diego, CA, 1983).

Organs in the Census: 204

Hits this month: 1,241

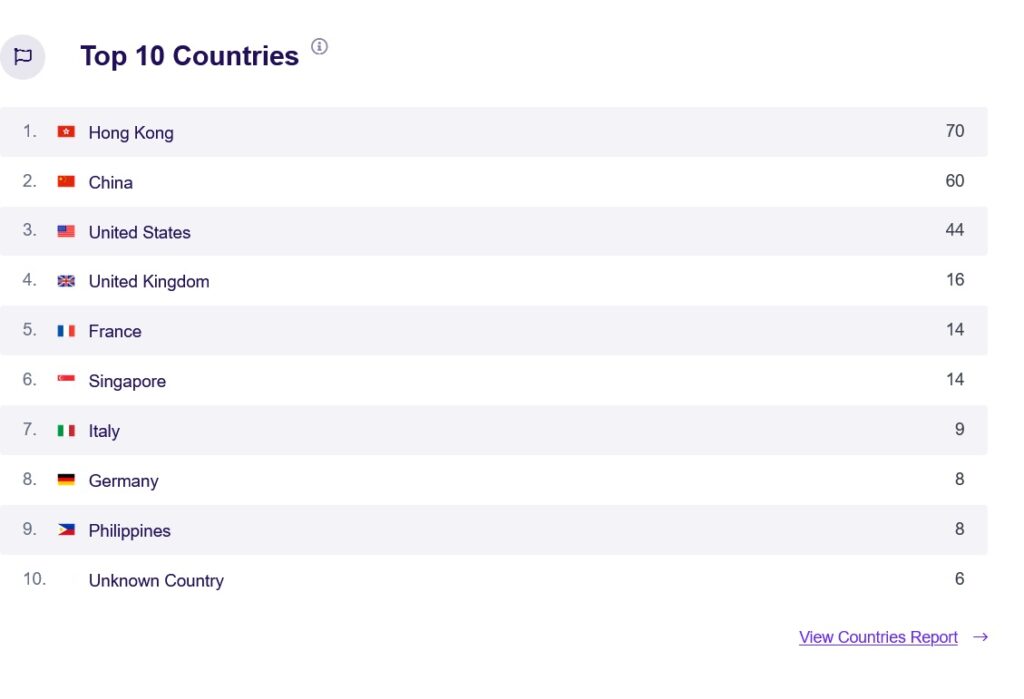

Top 10 Countries:

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for August 2023

31 August 2023

Minor fixes have been made to HKG1933a.

The Project understands that the erection of the new organ in the Cathedral of St. Ignatius at Zikawei (Xujiahui), Shanghai has reached the tuning and voicing stage. A dedication is planned for the last week of September.

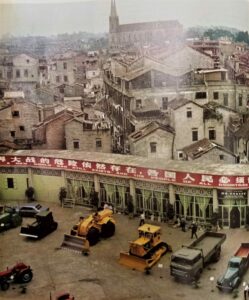

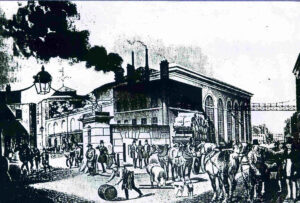

Photo(s) of the Month: The Cathedral of the Sacred Heart, Guangzhou (Canton) in 1973. Prof. Urrows writes:

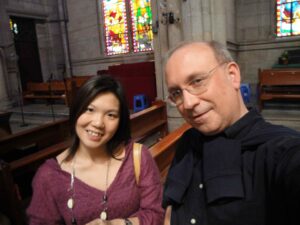

“I came across this photo in a September 1973 magazine, published exactly fifty years ago. This shows, in the background, the Cathedral, finished in 1888. The photo was taken in April 1973, on the occasion of the first Export Commodities Fair to be held in Canton since the start of the Cultural Revolution (which ended only in 1976). A large contingent of Western business people attended the fair (coming up by train from Hong Kong, which took 4 hours in those days). The ramshackle neighborhood was essentially the same when I first visited the church in October 1989, sixteen years later. When I last visited, in 2010, the neighborhood was under total demolition, a telling example of the domicide movement of the 1990s and 2000s (see second photo). The church had been renovated, with some tasteless stained glass added (see fourth photo, with the Project’s invaluable RA, Florence Cheng, standing next to me.)

“We have never been able to trace an organ in this church, but a 1917 report mentioned one. I have long thought this was probably a large harmonium.”

Organs in the Census: 203

Hits this month: 688

The neighborhood of the Cathedral in 2010, under demolition.

The 1888 Cathedral of the Sacred Heart.

Prof. Urrows with Florence Cheng, Cathedral of the Sacred Heart, 2010.

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for July 2023

31 July 2023

There are no updates to the Website or Census for July 2023.

We wish all of our visitors a pleasant summer holiday (if you have one), and remember to stay cool and hydrated wherever you are.

Organs in the Census: 203

Due to a problem with ExactMetrics, we are unable to give the number of hits this month, or the Top 10 Countries. We hope to be able to provide this data next month. Thank you for understanding.

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for June 2023

30 June 2023

There are no updates to the Census for June 2023. This month marks the fifth anniversary of the opening of the POCP Website.

However, word has reached the Project about the long-deferred installation of two new pipe organs, both now in train.

First, installation of the new Casavant organ (Op. 3925, IV/43 [54]) at the Cathedral in Macau will finally begin in December this year. This electro-pneumatic action organ was announced for installation in 2018, postponed to 2019. Logistic and structural problems, and then the COVID-19 pandemic and China’s “Zero COVID” policy, were responsible for four further years of delay. It is hoped that the organ will now be ready to be inaugurated in early 2024.

And the new Diego Cera Organ Builders’ III/34 instrument for St. Ignatius’ Cathedral at Zikawei, Shanghai, mentioned in What’s New for 27 February 2021, is now being installed with a projected completion and dedication date sometime in October this year. As the Project learns more about this, we will post further details.

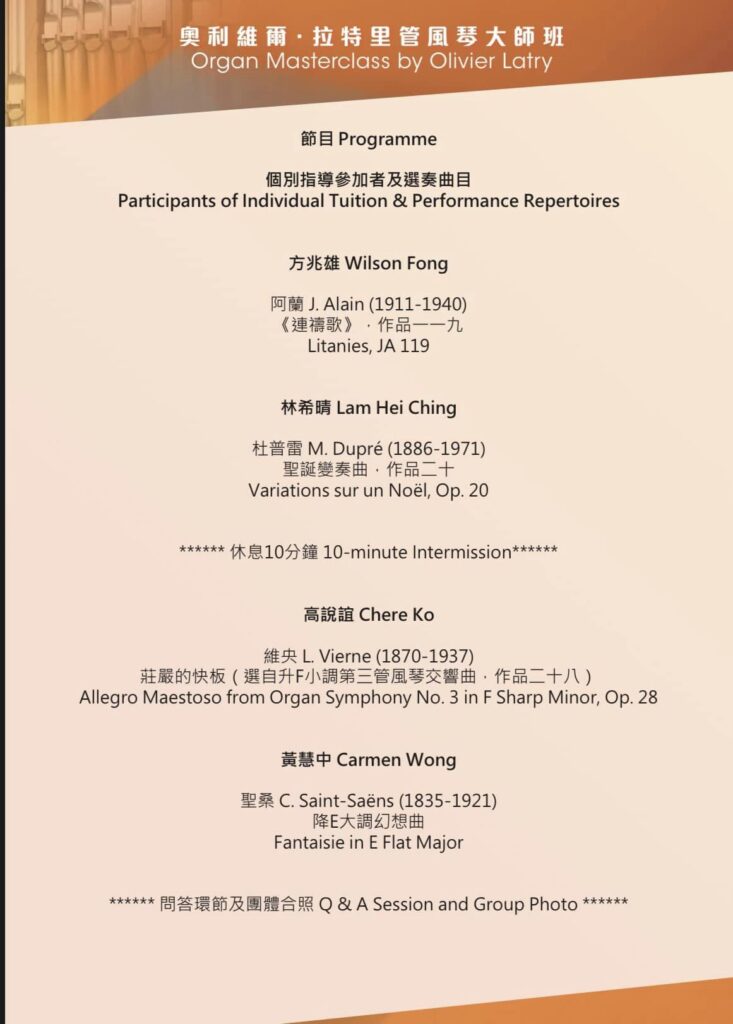

On the performance/education front, French organist Olivier Latry was in Hong Kong in early June to play Saint-Saëns 3 with the Hong Kong Philharmonic (the only organ+orchestra work they know, it seems.) While there, he also held a master class on HKG1989 for four local organists, all of whom chose works by late-Romantic and 20th C. French composers (see program below).

Organs in the Census: 203

(We have temporarily lost our ability to post statistics. Please check back next month.)

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for May 2023

30 May 2023

There are no significant updates to the website for May 2023.

We received a communication from Chung Chi College at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, regarding Peter Cheung Pei-dak. He was a Trustee of the College, and they confirmed his year of birth as 1911. Information about Peter Cheung, his experimental electronic organs, and his possible sighting of one of the bamboo organs of Ravary and Deleuze (FCW1931), was included in two What’s New posts in 2020 (updated) and 2018:

http://organcn.org/blog/further-thoughts-on-fcw1931/

The Project is grateful for this new information.

Organs in the Census: 203

Hits this month: 836

Top 10 Countries, May 2023:

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for April 2023.

29 April 2023

There are no significant updates to the POCP Website for April 2023. A new photo has been added to PEK2016a, and the page rearranged.

Vox Antiqua has begun to post some video clips from the Jesuita Cantat: Music from the Shanghai Missions ca. 1860 concert that took place as part of the Hymnos Festival in Hong Kong in November 2022, conducted by Project founder, Prof. David Francis Urrows.

The first of two clips available on their Facebook page is the well-known chant, O Filii et Filliae, sung in Mandarin Chinese in the 1780 translation by Jean-Martin Moyë MEP (1730-93). This was performed in the metrical plainchant version by Louis Lambillotte SJ (1797-1855), which would have been known to the Shanghai Jesuit community of the 1850s and 60s. It was mentioned in the letters of Fr. François Ravary, the mastermind of the ‘Bamboo Organs of Shanghai’, as having been sung in Shanghai under his direction.

The second work is Lambillotte’s own beautiful setting of Panis Angelicus. The links are:

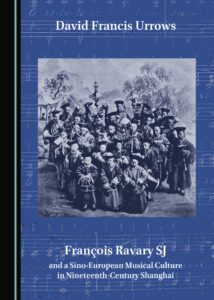

Prof. Urrows’ 2021 book, François Ravary SJ and a Sino-European Musical Culture in Nineteenth-Century Shanghai, on which this concert was based, has now been published in a paperback edition, at half the price of the hardcover book. Please see this link for ordering: https://www.cambridgescholars.com/product/978-1-5275-7461-8

A follow-up concert, Jesuita Cantat 2.0, is planned for this coming November in Hong Kong, featuring more music by Lambillotte, Chinese sacred music from the 19th C., the first Messe royale of Henry du Mont (1610-84) in the reconstructed 1857 Shanghai version, a work by Lambillotte’s student, Jules Dufour d’Astafort, and du Mont’s Cantate Domino. Stay tuned!

Organs in the Census: 203

Hits this month: 1,106

Please see our website visitors’ Top 10 Countries (including “unknown country”…) below.

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for March 2023

3 April 2023

We have received from our colleagues at Shanghai Pi Organ Industrial another nice photo of TAO1931. This photo, which was supplied by someone at St. Michael’s Cathedral in Qingdao, appears to have been taken in the 1940s, at least before late 1949 (see photo below).

An organ festival was held at the Gulangyu Organ Museum (now apparently the ‘Kulangsu Organ Arts Center’) and Xiamen Music School in Xiamen, Fujian Province. This took place over four days in late March, as part of the larger Kulangsu [Gulangyu] Music Week.

Organized and run by the organ department at Shanghai Conservatory, this featured FCW2017 in four concerts, two masterclasses, and an ‘organ course’. An event like this should be publicized more widely, but was not even known to the organ communities of the Hong Kong or Macau SARs, as far as we can tell.

The major academic event was a book launch for a Chinese translation (in simplified characters) of George Ritchie and George Stauffer’s 1992 Organ Technique: Modern and Early, by Shanghai Conservatory organ teacher Wu Dan (see photo below).

The Project apologizes for the late posting of the March updates, due to Prof. Urrows’ travel schedule.

Organs in the Census: 203

Hits this month: 1,067 (up 31% from last month)

TAO1931, seen from the nave in a photo from the 1940s.

Chinese translation (by Wu Dan) of Ritchie & Stauffer’s Organ Technique: Modern and Early.

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for February 2023.

26 February 2023

The Links page has been updated.

Minor updates have been made to HKG1984 and HKG1993. We appreciate the communication we received from our colleague Down Under, Carey Beebe.

Hits this month (899, of which 68% are new visitors)

Organs in the Census: 203

Picture of the Month: A team from Rieger dismantles NBO2018 in 2021. This vintage Hinners organ was damaged in a typhoon in late 2019. It is presently in storage, awaiting funding for its repair and re-installation. (Picture courtesy of Shanghai Pi Organ Industrial).

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for January 2023.

31 January 2023

The Pipe Organ in China Project wishes all our friends and visitors a Happy Lunar New Year of the Water Rabbit.

gung hei faat choi 恭喜發財/xin nian kuai le 新年快樂 !

The Errata list for Keys to the Kingdom has been updated.

We have received a series of communications from Shanghai Pi Organ Industrial Co., Ltd, the agent for Rieger in Mainland China, and new data from the Rieger firm in Austria with information about several new and old organ projects and installations.

The page for NTN2021 has now been updated, with the stop list. We were also advised of the installation, back in the summer of 2016, of a two-manual practice/teaching instrument at the Shanghai Conservatory, SHA2016. The latter organ is something of an inadvertent milestone, as it is the 200th organ in the POCP Census.

Another four-manual concert organ, Rieger’s second installation in Zhengzhou, has also been added to the Census as well, ZNJ2021.

We were further advised of three new organs under construction for a facility in Beijing (concert organ, practice organ, and positive). When these instruments are up and playing, we will report on them again. Additionally, we now have information and the specs of two Rieger Truhenorgeln (practice/continuo organs) installed in Shanghai and Hangzhou in 2005 and 2006 respectively (SHA2005b, and HCH2006b.)

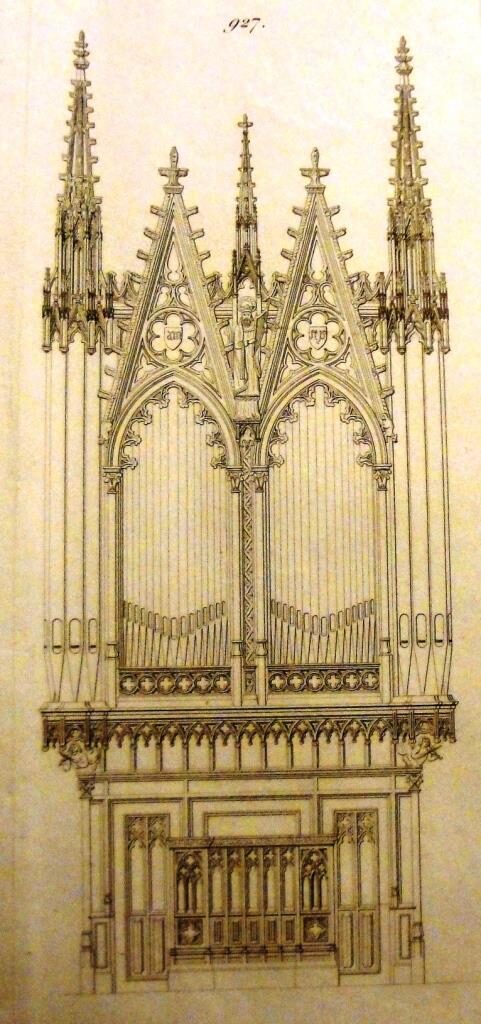

Particularly exciting among historical organs are a splendid photograph of the façade and console of the organ in St. Michael’s Cathedral in Qingdao (TAO1931), and a blueprint image of the façade of the later Rieger at Ichowfu (Linyi) ICF1936, along with the specs for both instruments.

Finally, we learned that the Wurlitzer theater organ sent many years ago from Australia to Xiamen’s Gulangyu Organ Museum will be renovated by Shanghai Pi Organ Industrial and Ian Wakeley, with a projected completion date in 2024.

And as if this were not enough about Rieger, for those of you with too much time on your hands we also accidentally discovered an online jigsaw puzzle of the console of SHA2005a https://www.jigidi.com/solve/b6s96sqs/rieger-organ-shanghai-china/

Hits this month: 1,109

Organs in the Census: 203

A look inside HCH2006b.

The Pipe Organ in China Project: Updates for December 2022

31 December 2022

There are no updates to The Pipe Organ in China Project Website for December 2022. Please see our top ten countries as of 31 December 2022!

We wish all our visitors and friends a Happy New Year 2023. 新年快乐!

Organs in the Census: 199

Hits this month: 581

The Pipe Organ in China Project: Updates for November 2022

30 November 2022

There are no updates to organs this month, but two events to report on which involve aspects of the research carried out by the Project.

The Hong Kong Hymnos Festival, founded in 2020, hosted a concert by the choir, Vox Antiqua, on 12 November 2022 at the Chapel of St. Ignatius (seats 550!) at historic Wah Yan College, Kowloon. A program of works based on the information contained in the letters of Father François Ravary, recently edited and published by Prof. Urrows, was performed: Jesuita Cantat: Music from the Jesuit Missions of Shanghai ca. 1860. Music by Ravary’s teacher, Louis Lambillotte SJ (1797-1855), and by his friend Hippolyte Basuiau SJ (1824-86), as well as Alfred Roland, César Franck, and Ernest Gagnon was performed. The main work was the Messe solenelle en style grégorien du Ve mode by Lambillotte (1854), performed for the first time in Prof. Urrows’ reconstructed edition. Three readings were given of excerpts from Fr. Ravary’s letters.

Father Ravary was the ‘mastermind’ behind the bamboo organs of Shanghai, including SHA1857, SHA1858, SHA1859, SHA1861, SHA1862, and SHA1881, which he designed and which were constructed by Brother Léopold Deleuze (1818-65).

As Lambillotte, Franck, and Deleuze were Belgian, the concert was honored by the presence in the audience of the Belgian Consul General in Hong Kong, Mr. David Lomastro, and his wife, as well as Belgian Consul Eva Morre.

On another topic, Prof. Urrows was recently invited to Good Hope School at Choi Hung, Kowloon, Hong Kong. He writes:

“Two of my former students teach at Good Hope School, and among other things they have a strong program in Chinese music and a sheng (笙) ensemble there. Father Ravary loved the sheng, although he couldn’t decide what its relationship to Western instruments of a free-reed type was (the relationship is tenuous and has been greatly exaggerated; and the sheng has no connection at all to the Western pipe organ).

“The small, traditional sheng which Ravary knew is now a kind of folk instrument. Technology has taken over, and following Western models has created an entire family of sheng of different pitch levels (soprano, alto, tenor, bass). The larger ones, in some instances (there is no standardization yet of the design of large sheng) start to take on aspect of a ‘steampunk harmonium’. I enjoyed hearing, among other things, the Hungarian Dance No. 5 by Brahms, arranged for sheng ensemble! Below are a few photos of my visit, with explanatory captions.”

Top 10 countries, November 2022:

Organs in the Census: 199

Hits this past month: 861

Apsara playing a traditional sheng, 8th C.

Alto sheng, front view. The upright tubes are resonators, not pipes.

Back view, showing bocal.

Back view, with panel removed showing elaborate wind tubes

A student playing the alto sheng. The key system is the same as on the hand-held soprano concert sheng.

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for October 2022

1 November 2022

The entry for HKG1919 has been revised, with additional information.

Photos of the Month: The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Hong Kong. This is the second building on the original site at Wellington and Pottinger Streets, Central. The first church, built in 1843, burned in 1859 and was replaced by the building seen in this old photo. In turn, a new cathedral (the present building) was built further up the hill on Caine Road between 1883 and 1888.

The old church was pulled down in December 1886, and the site today is occupied by commercial buildings and the Lok Hing Lane Sitting-Our Area. Entrance to the cathedral was by a flight of steps up from Wellington St, approximately on the site today of Welland House (62 Wellington St.) At present, 64-68 Wellington St. (the Yu Wing and Kai Wah buildings) have recently been demolished for new development. As always in Hong Kong, there has been absolutely no attempt made to survey the site archeologically (see second photo), or to make provisions for the discovery of relics and other historical artifacts.

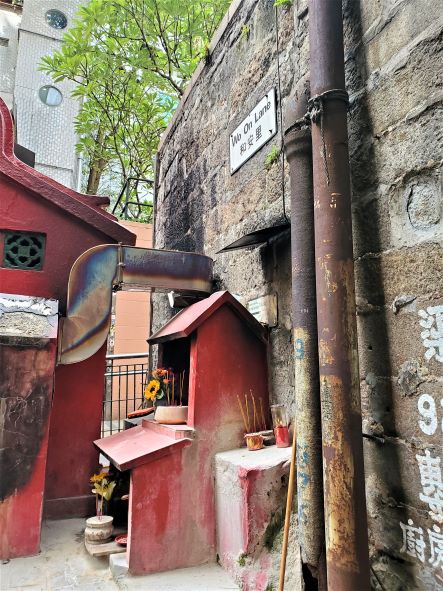

Access to the former Cathedral site (third photo) is now from Pottinger St. via the western end of Lok Hing Lane, or from the Wellington St. (north) entrance of Wo On Lane (fourth photo). The retaining wall along the western side of the passage abutting 60 Wellington St. is possibly of the same date as the second church. Behind this building, at the level of Lok Hing Lane, is a curious, cement-covered fragment of an old brick wall, which may also be a relic of the church (fifth photo).

This was the church of Bishop Giovanni Timoleone Raimondi PIME (1827-94), Vicar Apostolic of Hong Kong, still remembered today by a Hong Kong school named in his honor, and various other Raimondi place names. The church had no organ that is known of, but a harmonium and an organist who, according to the Bishop, “plays only waltzes and polkas, because he says he has no [scores of] sacred music.” In 1878, Bishop Raimondi obtained a subscription to the Cecilianist journal, Musica Sacra, and asked for some appropriate organ music, and also “for some masses by our serious music composers.” Such was musical life on the China Coast in the 1870s.

Recently, there was an interesting post on Facebook by the group, Hong Kong Heritages, about the cathedral.

The second Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Wellington St., Hong Kong, 1860s-70s.

Construction on Wellington St., October 2022, on the site of the former cathedral. Wall of Welland House (62 Wellington St.) on the left.

Wo On Lane (north entrance) and retaining wall, possibly related to the cathedral.

Lok Hing Sitting-Out Area (looking East), on the site of the crossing and altar area of the cathedral.

Fragment of a brick wall along Lok Hing Lane, possibly connected to the cathedral.

Organs in the Census: 199

This month’s hits: 1,080

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for September 2022.

30 September 2022

Our colleagues at Casavant have informed us of an installation in Beijing, dating back to 2016 when they installed three other organs in the Chinese capital. This two-manual practice organ, now at CCOM, is a relocated organ originally built for McGill University in Montréal in 1962, and has the Census identifier PEK2016d.

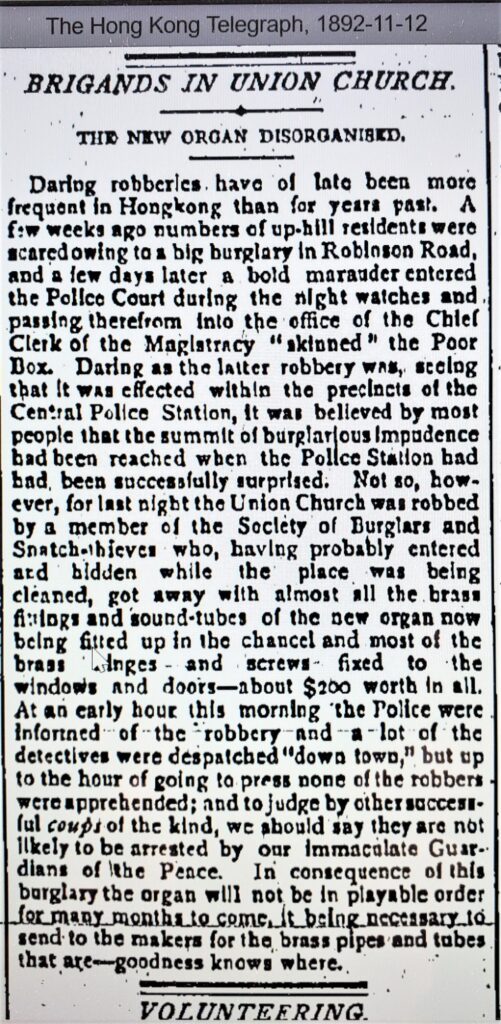

HKG1860: “Brigands in the Church”, and the Disorganized Organ.

Prof. Urrows writes:

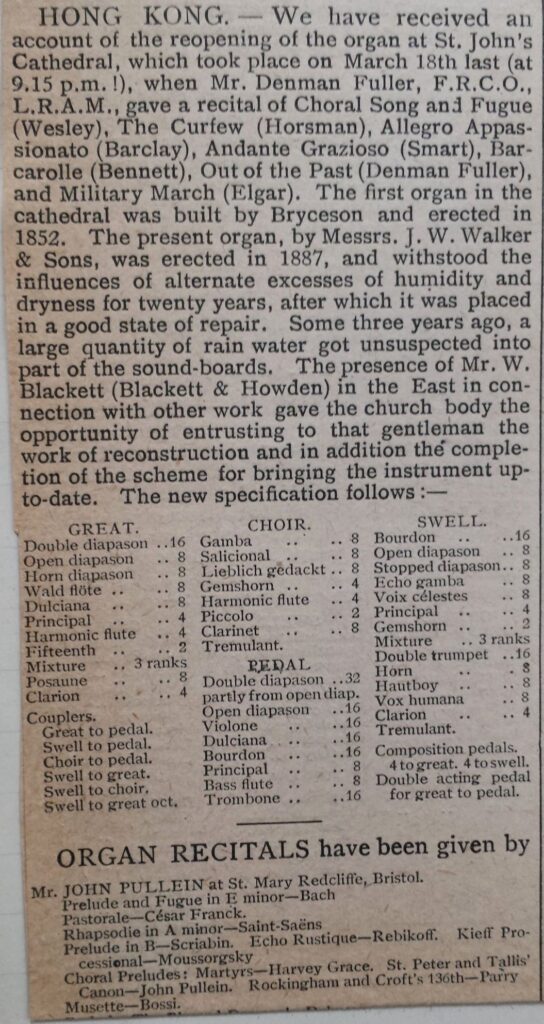

HKG1860 was the Bryceson and Son organ installed at St. John’s Cathedral, Hong Kong, and removed when the new Walker organ (HKG1887) was installed. After several years of debate over what to do with it, it was sold in 1890 to Union Church, to be reinstalled by Walker in the new church building on Kennedy Road. It served there until 1917 and the subsequent installation of the Blackett and Howden organ (HKG1917) that occasioned William Charlton Blackett’s personal visit to Hong Kong, from which place he never left.

This summer, I came across a fascinating news item in the Hong Kong Telegraph for 12 November 1892, that rewrites, perhaps, a little bit of this story. Apparently, on 11 November there was a robbery at Union Church, and the thieves “got away almost all the brass fittings and sound-tubes of the new organ now being fitted up in the chancel.” It is a little difficult to interpret this, as the organ was not new, and ‘sound-tubes’ could mean pipes, but these would not, of course, be made of brass. Perhaps these were conduits for a possible conversion to pneumatic action.

The news story (see below) goes on to say that “In consequence of this burglary the organ will not be in playable order for many months to come, it being necessary to send to the makers for the brass pipes and tubes that are – goodness knows where.”

Again, it’s not entirely clear just what was taken in the robbery. Does this mean that HKG1860, although sold to the new church in 1890, was not actually erected until the middle of that decade? Was Walker (still) doing the work in late 1892? And what of the report I found this summer, that in the Autumn of 1896, Vittorio Facchetti was invited to work on the Union Church organ at the time he was erecting his enormous masterpiece, HKG1896, over at the nearby Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception? And in what sense does this impact the fact that this organ was again completely rebuilt by the Hong Kong branch of S. Moutrie & Co. in 1907-08?

Finally, the police estimate of the total loss at the church, including the non-organ parts, was “$200”. This refers to the ‘dollar Mex’, which was the accepted currency at this time, and it appears this would have been equivalent to about 35 GBP in 1892. This relatively small sum (in the scheme of the cost of a pipe organ) suggests that not all that much was actually taken, but doesn’t resolve the question, when was HKG1860 finally ready for use at Union Church? Research never ends!

Organs in the Census: 199

Hits this month (September 2022): 701

The Pipe Organ In China Project: Updates for August 2022

31 August 2022

Updates have been made to PEK1719, HKG1860, HKG1917, and HKG1919. Several new links have been added to the Links page.

The Hong Kong Chapter of the American Guild of Organists held a Summer Organ Academy for Adults in July and August. The final students’ concert was held on 21 August on HKG1986 at the Academy for Performing Arts, and included works by JS Bach, Boëllmann, Geoffray, Karg-Elert, Mathias, Felix Mendelssohn, Schack, Stanford, Louis Viérne, and René Vierne, played by 10 of the participating students.

After some period of debate, The Project has decided to include the playable pipe organs presently at the Gulangyu Organ Museum in Xiamen, Fujian Province, in the Census (FCW2017 was already added some time ago.) While these organs have nothing historically to do with China (other than that they are found at present in Xiamen), the fact that they are present is enough, we have concluded, to include them in the Census, just as those that no longer exist, or which have left China, are similarly included. As with the relocated organs in Beijing, Tianjin, and Ningbo, these organs will receive a Census date reflecting their installation in China when confirmed, and not that of their original construction. We have added FCW2005 to the Census this month. The other two pipe organs of which we are aware (a Mackenzie, Lee & Kaye, originally built in 1874 and enlarged several times, and a Wurlitzer Model H of 1928, both ex-Australian installations), have not yet been confirmed as actually up and working at the museum.

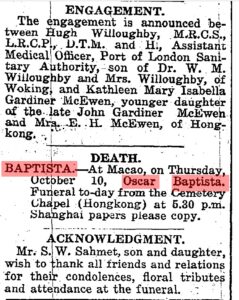

The discovery of HKG1896 this summer led Prof. Urrows to do a bit of research on Oscar Crispim Baptista (1861-1929), organist at the Roman Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception from at least 1888 to his death in 1929. He reports as follows:

As far as I can tell, Baptista was born in Macau, which means that he was a Portuguese national. It is of course possible that somewhere in his family there may have been some Japanese or Chinese forebears (the China coast term, ‘Portuguese’, commonly meant in the 19th and early 20th centuries a person of mixed ethnicity). But just how long his family had been settled there is at present unknown. Baptista turns up on the 1895 juror list for Hong Kong, living on Elgin St. in present-day Central, although it is known that once he married, he moved to Hart Avenue in Kowloon. At any rate, he seems to have come to Hong Kong as a relatively young man.

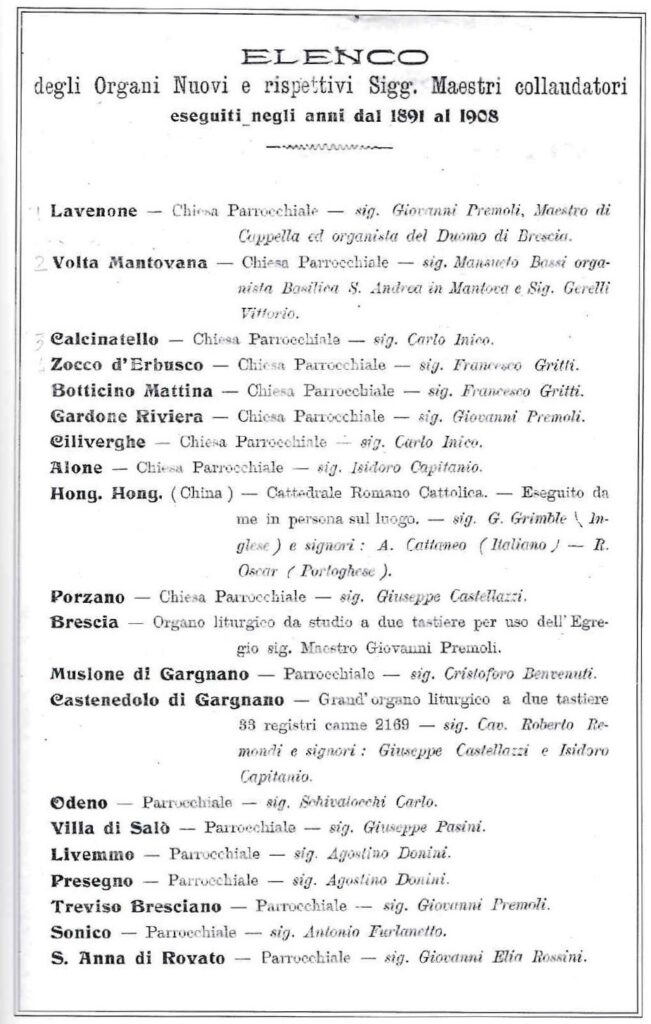

Baptista worked for a brokerage company, Gibb, Livingston & Co., and what musical training he had is unrecorded. Baptista is the “R. Oscar” mentioned by Vittorio Facchetti as one of the ‘collauditori’ (testers) of the completed 1896 organ at the Roman Catholic cathedral. Why Facchetti referred to him in this way is not known, but he may have thought he was a priest (‘R.’).

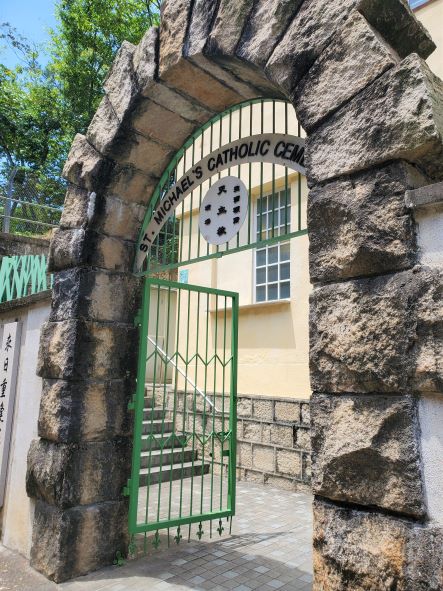

His brief obituary notice (in the South China Morning Post, 11 October 1929, see below) shows that Baptista died in Macau. But he was in fact buried in Hong Kong. I might add, that I found that I share a birthday with Baptista, 25 October. This is the Feast of St. Crispin (and St. Crispinian), whence Baptista’s interesting middle name, Crispim. I only discovered this by dragging myself in the heat of a Hong Kong summer to St. Michael’s Cemetery in Happy Valley, and locating Baptista’s tomb (and that of his wife, mother-in-law, and only son, see photos below).

Organs in the Census: 198

Hits this month (August 2022): 619

Obit for Oscar Crispim Baptista.

St. Michael’s Cemetery, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

Gate at St. Michael’s Cemetery

Baptista family tomb, St. Michael’s Cemetery.

Names of Baptista’s mother-in-law and wife.

Baptista plot, St. Michael’s Cemetery.

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for July 2022.

31 July 2022

HKG1896: with the discovery of this Bianchetti e Facchetti organ in the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Hong Kong, the old page for the spurious HKG1888 has been kept online, but substantially altered; and necessary changes have been made to HKG1921 and a few other posts. Prof. Urrows posted a two-part blog essay, “The Phantom of the Organ Loft”, during July to explain the complex situation with these organs (see What’s New). The Project also appreciates the help of Sig. Massimiliano at organibreschiani.it for help with unraveling this complicated story. https://organibresciani.org/index.php

In yet another exciting development, a previously-unrecorded organ (HKG1872) by William Hill & Son of London has been located, and presumed installed in Hong Kong in 1873 in St. Peter’s Church, West Point. This organ is the second (or third) pipe organ known to have been installed in the British Crown Colony, and fills a gap in the record between the Bryceson (HKG1860) and Walker (HKG1887) organs at St. John’s Cathedral. The project appreciates the help of the British Organ Archive, Hannes Ludwig, and John Richard Maidment, for their help in locating this installation.

Word has also reached The Project about a planned new pipe organ for the Shenzhen Conservatory of Music (est. 2020, and operated by the Chinese University of Hong Kong.) Further details will be posted when we have them.

The China Top 10 Pipe Organ List:

Statistics, statistics, statistics: there are at present 197 organs in the POCP Census, with several pending installation which has been delayed by the COVID epidemic.

This month we looked at the breakdown of organ locations and numbers, and here are the Top Ten locations for all historical and current pipe organs in China, along with the date of the earliest-known installation or construction.

|

Beijing (PEK) |

50 | 1611 |

| Hong Kong (HKG) | 45 | 1847 |

| Shanghai (SHA) | 24 | 1856 |

|

Macau (MAC) |

12 | 1600 |

| Tianjin (TJN) | 9 | 1904 |

|

Fujian/Fuzhou (FCW) Tie with Qingdao (TAO) |

6 |

1631

1909 |

| Guangzhou (CAN) | 5 | 1678 |

| Hangzhou (HCH) | 4 | 1919 |

|

Chengdu (CHD) Tie with Shenyang (MKD) |

3 |

1910

1912 |

The sum of these 11 locations (there are two ties, each counted together as 1.5) equals 167 of the 197 pipe organs in the Census, or 85% of all the pipe organs ever known to have been installed in China. Only four reach double digits. All other places in China with pipe organs have only 1 or 2 reported. The earliest date of first installation in this top ten list in MAC1600, the latest HCH1919.

This list makes no distinction between organs that exist, or those that don’t exist anymore. If the data were sorted into pre- and post-1949 pipe organs, and excluded those that either no longer exist, have left China, or are pending installation, the results would be, and be sorted rather differently.

Photo of the Month: While on the topic of Top Ten statistics, here is an interesting screengrab from 30 July 2022. This shows the top ten locations from which hits on the website come, according to Google’s Exact Metrics (all data on this chart is from Google, not from the POCP.) We were rather surprised to see Indonesia at #3, especially as there isn’t a very strong pipe organ culture there at present. We will be keeping track of these statistics, and post again if any particularly interesting trends become evident.

Organs in the Census: 197

Hits in July 2022: 769 (66% new visitors; 34% returning visitors)

The Phantom of the Organ Loft, Part Two: HKG1896 and its dedicatory recital.

7 July 2022

For Part One of this series, see What’s New for 6 July 2022.

Prof. Urrows writes:

Because in-depth accounts of organ inaugurations in China are fairly uncommon, it’s worth presenting the Hong Kong Daily Press report (29 August 1896) of the first hearing of Bianchetti and Facchetti’s HKG1896 in full. I have worked on identifying the people mentioned here, especially for the benefit of those who do not live in Hong Kong or have any historical knowledge of people and corporations in the former British Crown Colony (1842-1997).

James Orange (1856-1927) was an architect/engineer, and after working for the Hong Kong Brick and Cement Co., he was a partner in the Hong Kong architectural firm Leigh & Orange, founded 1874 and still in business. The firm built many famous buildings and waterworks in Hong Kong.

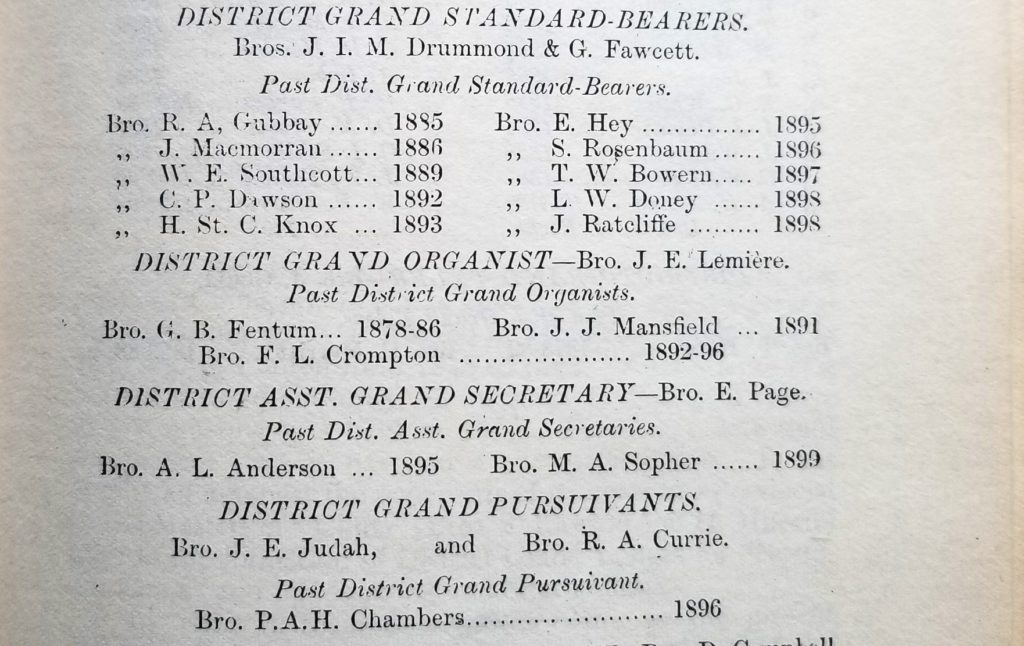

George Grimble (1867-1933) was born in Hong Kong and worked in what we now call ‘logistics’. Like James Orange, he had a ‘day job’. As reported here, he was a student of organist Frederick (F.A.) Sangster (?-1902), who was the first titular organist of St. John’s (Anglican) Cathedral in Hong Kong. Sangster in turn was a student of Sir Frederick Gore Ouseley (1825-89), who wrote the famous anthem, “From the rising of the sun”, and who had recommended Sangster for the Hong Kong position. Grimble was organist at Union Church, which I think is how Sig. Facchhetti came to be asked to do repair work on the Bryceson organ (HKG1860) in that church. He also is reported playing at St. Peter’s West Point (to be the topic of an upcoming post), and was a Mason as well, and the local lodge’s ‘grand organist’. This raises the interesting question as to whether the Masons in Hong Kong had a pipe organ.

Fr. Angelo Cattaneo (1844-1910) was a PIME missionary who had worked in Mainland China before being called to Hong Kong in the 1880s as procurator of the Diocese. He was later (1905) made a Bishop and Vicar Apostolic of Southern Henan (based in Hankou, part of present-day Wuhan, where the COVID epidemic started!)

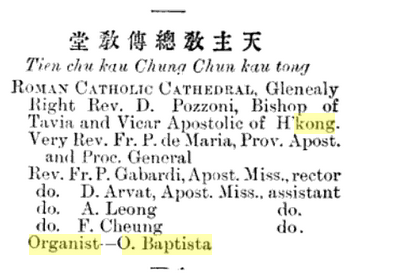

‘O. Baptista’ was Oscar Crispim Baptista (1861-1929), a Macanese musician who worked for the trading house of Gibb, Livingston, & Co. He was organist at the Cathedral from its opening in 1888 well into the 20th C. (see pic below). After his death, his talented daughter Aurea took over as cathedral organist.

Lane Crawford Ltd. is a department store in Hong Kong, founded in 1850 and still in business today. G.L. Duncan was an employee in a middle management position in the 1890s. Since Lane Crawford handled furniture sales, he probably had some knowledge of cabinetry and carpentry.

Of the six singers, two were obviously Portuguese: but Carvalho and Graça are very common names, difficult to identify. The Portuguese ‘Club Lusitano’ had held fund-raisers for the organ starting in 1889. The Club is still active in Hong Kong, and The Project plans to ask if they have any records from this period, despite a lot of things such as paper records having been destroyed in 1941-44, during the Japanese Occupation of the colony. Of the two Dutch singers, A.C. Van Nierop worked at some point for the brokerage firm Benjamin, Kelly, and Potts in Shanghai before moving to Hong Kong. Kraal may actually have been born in Macau to Dutch parents, but this is still uncertain (I have unearthed a Lavinia Eulalia Krall, born in Macau 14 March 1853, which is about the right date for a sister of the singer.) I have not uncovered anything about Mr. Sliman who was probably Scottish, though Sliman is derived from a Dutch name. All these people may just have been members of the cathedral’s choir. Mrs. Hagen’s name turns up in numerous concert reviews in Hong Kong newspapers of this time. She was married to an Edward James Hagen, who was a partner in Stolterfoht and Hagen, “agents and commission brokers”. He died shortly after this concert, on 26 February 1897, and is buried in the Colonial Cemetery. His widow continued as a singer in Hong Kong, especially in performances at St. John’s Cathedral.

Finally, the reviewer seems to have got some things wrong. The organ was a two-manual instrument, and his complaints seem to be oblivious to an obvious hypothesis: that only the Great manual of the organ had been installed at this date. The organ, according to research in Italy, was built in 1895, so it could not have arrived in 1894. It probably came in early 1896, and sat unerected while the Lane Crawford crew tried to figure out what to do with it. A sentence in the review was transposed by the typesetter, and I have silently fixed this error here. The reviewer was also unaware of the existence of traditional Portuguese guitar/mandolin ensembles (which he calls here an “orchestra”), and these are still to be found today, even in Macau. The music of James Orange, and Fr. Cattaneo, seems to have disappeared at the present date, but it is surprising to see several recently-composed works on the program as well.

Organ Recital at the Roman Catholic Cathedral – Hong Kong Daily Press, 29 August 1896

On Thursday evening [27 August 1896] an organ recital was given at the Roman Catholic Cathedral to celebrate the opening of the new organ. The cathedral was crowded and the general opinion was that the recital was a great success. The organ is a low-priced single manual and it was made in Italy. It has, considering the comparatively small sum of money spent upon it, and exceedingly good tone, and a bargain was certainly struck when the purchase was made. The instrument was sent to the colony over two years ago and with it came complete plans of each stage of organ building, which were sent to Messrs. Lane, Crawford & Co. Mr. [G.L.] Duncan was deputed to erect the organ, but unfortunately, he was unable to finish the work because many of the pipes were broken and twisted in transport. It was therefore decided to send to Italy for a special man, and Mr. Vittorio Facchetti, of Brescia, came here to complete the erection of the instrument. He had many difficulties to overcome in the work, and it says much for his ability that the organ now possesses such a good tone; in fact, his work has been so much admired that he was appointed to repair the organ at the Union Church [HKG1860].

The recital opened with a Grand March Offertoire in F which, was composed by Mr. [James] Orange and arranged for the organ by Mr. [F.A.] Sangster, the late organist at St. John’s Cathedral. The piece was played by Mr. G[eorge] Grimble, who is to be congratulated upon his excellent performance, more especially as the music was arranged for an organ with two manuals. The remark concerning Mr. Grimble’s difficulty in playing on a single manual applies of course to Mr. Cattaneo [PIME] as well. Every one praised Mr. [Angelo] Cattaneo’s playing; indeed, he really astonished most of his friends, who were not aware that he was such an accomplished organist. It was indeed a first-class performance that Mr. Cattaneo gave, particularly in the Monastic Coro, in which the flute stop was splendid. Mr. O. Baptista, the organist at the cathedral, also presided at the instrument and gave satisfaction.

The vocal selections were, for the most part, well rendered. Miss Carvalho sang exquisitely, and Mr. C.H. Graça was also in good voice, but the accompaniment was too soft. Mr. Sliman was evidently suffering from a cold and should not have sung. Mrs. Hagen gave Mascagni’s Ave Maria in excellent style, and the duet singing of Messrs. Van Nierop and Kraal was much enjoyed. A number of amateurs gave two selections on mandolins and guitars. They played well, but it would have been better if chorus singing had been substituted. It should be added that the cathedral possesses exceptionally good acoustic properties, perhaps the best in the colony; and the organ well-filled the building, while the vocalists could be heard very distinctly. We must congratulate our Roman Catholic friends on the possession of such a beautifully-toned instrument. We can only say one thing against it, and that is, it is a pity it does not possess fewer stops and a double [second] manual. The following was the programme:

Grand March Offertoire in F (composed for the occasion), by Mr. J[ames] Orange: Mr. G. Grimble

“Inflammatus” – for soprano, from Rossini’s Stabat Mater: Miss Carvalho

Barcarolle – for orchestra of mandolins and guitars: Lady and Gentlemen Amateurs

Monastic Coro, in distance; and Duet for Flute and Clarionet, [arr.?] for organ, by Maestro A. Cattaeno

Salve Maria – for Baritone, by [Saverio] Mercadante: Mr. C.H. Graça

Pastorale – J.S. Bach: Mr. O. Baptista

[The] Nun’s Prayer – [Charles] Oberthür [op. 54]; Mr. O. Baptista

Offertoire from the Messe de Mariage – Théodore Dubois: Mr. G. Grimble

“Cujus animam” from Rossini’s Stabat Mater: Mr. D.K. Sliman

Serenade – for orchestra of mandolins and guitars, by [Charles] Acton: Lady and Gentlemen Amateurs

Ave Maria – for soprano by [Pietro] Mascagni: Mrs. Hagen

Qui tollis, and Qui Sedet, for Bass [solo]; Laudamus te for Tenor [solo]; Christe [eleison], duet for Tenor and Bass, from Mass No. 8 by A. Cattaneo: Messrs. Van Nierop and Kraal, accompanist Maestro A. Cattaeno

Solo for Tromba [and organ?], and Marcia Finale, for organ, by Maestro A. Cattaneo

1908 entry for the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Hong Kong, in the “Directory & Chronicle for China &c.”

The Phantom of the Organ Loft, Part One: HKG1888 and HKG1896

6 July 2022

‘Questions about the sources of our knowledge [have] always been asked in the spirit of: ‘What are the best sources of our knowledge—the most reliable ones, those which will not lead us into error, and those to which we can and must turn, in case of doubt, as the last court of appeal?’ I propose to assume, instead, that no such ideal sources exist—no more than ideal rulers—and that all ‘sources’ are liable to lead us into error at times. And I propose to replace, therefore, the question of the sources of our knowledge by the entirely different question: ‘How can we hope to detect and eliminate error?’”

Karl Popper, ‘Conjectures and Refutations’.

Prof. Urrows writes:

All sources are liable to lead us into error at times. People who know me, know what a profound influence the ideas and writings of the 20th C. Anglo-Austrian philosopher, Karl Popper (1902-94) have been in my life. Here, The Project has to turn to Popper to explain the removal of one organ from the Census (although it will continue to have a ‘phantom’ presence, because it is described at length in Keys to the Kingdom), and the addition of a newly-documented instrument that effectively and physically takes its place.

The error involves HKG1888, the G.W. Trice organ which we have placed for 30 years at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Hong Kong. The source which led us into this error, is a history of the Trice organ company of Genoa, La Fabbrica d’Organi di William George Trice, 1881-1897, by Maurizio Tarrini (Savona: Editrice Liguria, 1993). From this book, comes the information that Trice (1848-1920) prepared, and then revised a proposal for an organ for the new Roman Catholic Cathedral in Hong Kong in 1882 (although the Cathedral was not opened for another six years), at a cost of 22,000 francs. In the end, it now appears to have proven to be too much money for the Apostolic Prefecture of Hong Kong to raise (Hong Kong did not become a diocese until 1946). In any event, the procurement of the organ was from the start a competitive tender exercise, under the direction of Fr. Bernardo Viganò (1837-1901). Trice’s progetto, then, was only one of the bids received; and even after the Cathedral was opened, on 8 December 1888, there was to be no organ (except, perhaps, for a harmonium) for another eight years.

Late last month, in going through the Hong Kong newspaper, Hong Kong Daily Press, for 29 August 1896, I came across an account of the dedication of the organ that was finally—only in 1896—installed in the Cathedral. I will give an annotated version of this news article in Part Two. On looking into this further, I found that almost contemporaneous with my own inquiries at the Diocesan Archives in Hong Kong about six years ago, a group of several organ historians in Brescia, Italy, had also made inquiries and had come up with data which for some reason I never saw. This is what actually happened:

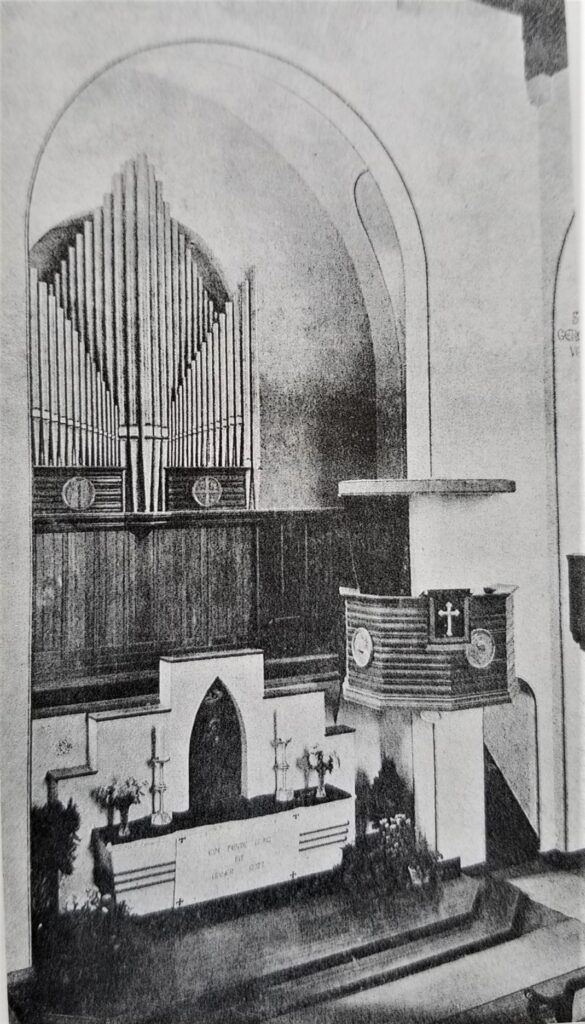

The organ for the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Hong Kong, then, was in fact built by the firm of Bianchetti e Facchetti, of Brescia. It was a two-manual and pedal instrument with 55 stops, and thus the largest organ installed anywhere in China until HKG1989, nearly a century later, and the largest instrument Bianchetti e Facchetti ever built. It was later rebuilt by Blackett and Howden about 1921, when and additional manual and five stops were added, bringing the total to 60/III. The organ, according to the 1896 news report, was shipped to Hong Kong in 1894 (this may be a mistake; it appears they began building it in 1895, and in fact it arrived sometime in early 1896). On opening the packing cases, it was found that most of the pipes and the rest of the organ had been damaged in transit. Local attempts to erect the organ failed as a result, and Vittorio Facchetti (1859-1931) himself had to come to Hong Kong in mid-1896 to repair the damage and finally erect the organ. It was tested and approved by George Grimble (1867-1933, organist at the interdenominational Union Church on Kennedy Road), Fr. Angelo Cattaneo (1844-1910, procurator of the Prefecture, and an experienced organist and composer), and Oscar Baptista (1861-1929), a Macanese who worked for Gibb, Livingston, & Co., and who had been organist at the cathedral since its opening in 1888. In a 1908 Elenco of his recent installations (see below), Facchetti proudly mentioned that HKG1896 had been “eseguito da me in persona sul luogo” – ‘installed by me personally on the spot.’ Facchetti and Grimble seem to have got on well, and Facchetti was then asked and made some repairs to the organ at Union Church (HKG1860) at this time.

For the dedicatory concert on 27 August 1896 (see Part Two), it appears that about half the mechanical action organ was ready, with the Grand’ Organo (Great) and Pedal divisions in place, and the Organo espressivo (Swell) installed at a later time, probably by early 1897. We may hypothesize that Facchetti had to send back to Italy for additional parts and pipes, all of which greatly delayed the work. The full specs are now available at HKG1896 (a date I have chosen for ‘first report’, and certainly this was the date of the dedication of the instrument, no matter that it may not have been fully erected at this point.)

The discovery of this instrument means that certain assumptions about the succeeding instrument by Blackett and Howden (HKG1921) have to be reconsidered; and that the organ case now standing in the Cathedral is unlikely to be the original Bianchetti e Facchetti case. It has ducts for pneumatic tubes, and doesn’t look anything like the surviving organs from the Italian builders. It was probably built by Blackett and Howden, perhaps even in Hong Kong from locally-sourced woods. This is a new point of inquiry for The Project.

In Part Two, I will present the 1896 review of the dedicatory concert with annotations (the journalist doesn’t seem to have got all his facts right.)

The Project is most grateful to Sig. Massimiliano of Organibresciani.it for his help with documenting this research and this organ, and whom we thank for the images below.

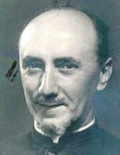

VIttorio Facchetti (1859-1931). Photo courtesy of organibreschiani.it.

Facchetti’s 1908 “Elenco”, with the erroneous “Hong.Hong.” location of HKG1896.

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for June 2022.

30 June 2022

June 2022 marks the fourth anniversary of the opening of The Pipe Organ in China Project Website, and for once it has been a busy month at The Project.

The page for HKG1860 has been updated, with new information and an interesting news clipping from 1867.

A major discovery this month involves the installation previously numbered as SHA1883b. It turns out that this organ was installed much earlier than 1883, and we have located a report of the instrument dated 1865, which means that it was probably built by Henry W. Knauff, Sr. (and not by his son, Henry Jr.). Even this date is really too late: we know from the same report that it was installed somewhat earlier than this, and was only moved in 1865 from the organ gallery of the Church of Our Savior, Hongkou, Shanghai, to a place on the left side of the chancel during a renovation of the building after the Taiping Rebellion (1850-64). A much-later photo of the organ in this location has also surfaced, one that shows that it was a two-manual instrument with about 12 stops. In consequence, it has been renumbered SHA1865 in the Census (date of first report).

The Project is also working on confirming the installation of two hitherto unknown pipe organs in Hong Kong, one by William Hill & Son, of London, apparently ordered and sent to Hong Kong in 1872, and the other by the Italian firm of Bianchetti & Facchetti of Brescia in 1896. Further details will be forthcoming.

The page for HKG1980 has been updated, after an inspection of the dismantled organ by Prof. Urrows earlier this month in a warehouse facility in Kowloon, Hong Kong. The specs are finally known and reported, including the fact that it is (only) a one-manual instrument.

Pages for HKG1917, as well as HKG1979 and its successor, HKG2012, have also been updated, based on new information.

A blog post by Prof. Urrows was posted on 10 June, concerning an early report in English of SHA1857, written by the American Episcopal missionary, Edward W. Syle.

JL Weiler Inc. the Chicago-based firm specializing in organ rebuilding and restoration, has reported that their work on the rehab of PEK1920 has been completed, and now everything is being sent to Casavant for further work and re-erection. Visitors to this website may recall the announcement of the rebuilding of the 1920 Kimball organ at PUMC from the December 2021 Updates. Photos of the newly-provided console (the original one was destroyed, along with the reproducer, by 1966 at the latest) can be seen on Weiler’s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/jlweilerinc/posts/3292526844310325

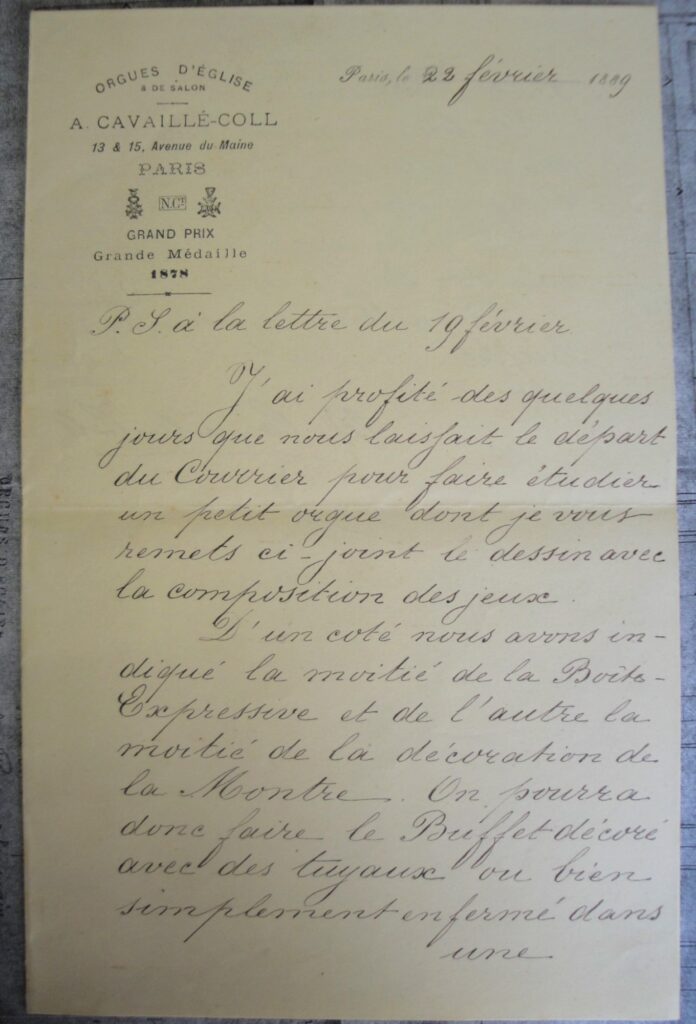

Photo of the Month: Aristide Cavaillé-Coll writes to Msgr. Alphonse Favier CM, Grand Vicar of Beijing, in February 1889, about an orgue du chœur for the Beitang (North Church):

“Paris, 22 February 1889.

P.S. to the letter of 19th February:

I’ve taken advantage of a few days left to us before the departure of the mails, to design a small organ for which I attach here the plan along with the specifications.

On one side [of the plan] we have shown half of a swell box, while on the other side the [alternative] decoration of the façade with the pipes. One can thus make a case with pipes decorating the front, or more simply enclose it all in a swell box. [To save money, Favier may have told Cavaillé-Coll that he planned to make the case in Beijing, as had been done with PEK1888].

At all events, it would be best [for you] to wait for the arrival of the organ before building the case.

The total cost of making this organ with a case would be 5,000 francs; without a case, 4,000.

A[ristide]. Cavaillé-Coll.”

In the end, Bishop Favier argued the price of PEK1890 down to 3,000 francs, but it is not known if the case (without the expression box) was made in Paris, or in Beijing. The latter seems more likely, given the bargain price.

The original letter, along with the plan, is at the Archives Lazaristes (Archives of the Congregation of the Mission) in Paris.

Organs in the Census: 195

Because of changes with WordPress and our domain host, we cannot get statistics for hits beyond the past 30 days any more. For the record, there were 824 hits in June. However, some other interesting data seems to be available now, and we will begin to present this in July updates. Thanks to all our visitors for understanding.

An early English-language account of SHA1857: Edward W. Syle and ‘The Bamboo Organ of Tungkadoo’

10 June 2022

Prof. Urrows writes:

Readers of Keys to the Kingdom, and some visitors to this website will understand how important an installation SHA1857 has been to The Pipe Organ in China Project. A casual inquiry about this instrument led to the creation of The Project in 1989, and it continues to be our mascot, our totem, our starting point and origin.

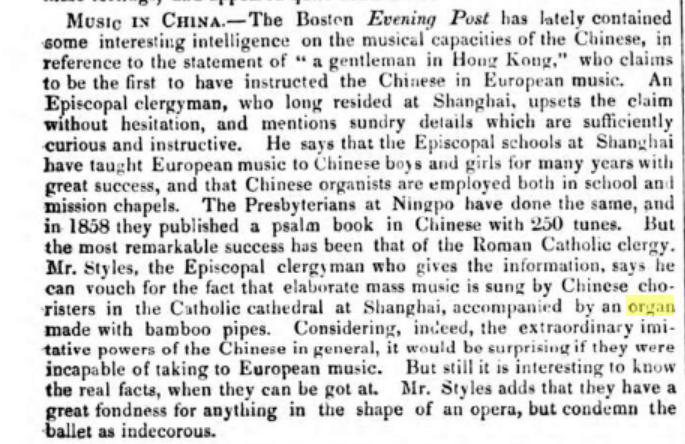

Recently, while looking for something else, I came across a news clipping that appears to contain one of the earliest English-language mentions of SHA1857. This appeared in an issue of the newspaper, The London and China Telegraph, which was published in London and ran from 1859 to 1921. The paragraph in question (quoted from an earlier issue of the Boston Evening Post) appeared in the issue for 28 July 1867 (it was a weekly paper), and so ten years after the construction of SHA1857. Here it is:

The first thing I noticed was the name of “Mr. Styles, the Episcopal clergyman.” Just as some of my Roman Catholic readers have been shocked to discover that Fr. Ravary and Br. Deleuze made many visits to Holy Trinity (Anglican) Church to inspect and study the two-manual and pedal Gray and Davison organ (SHA1856) while planning SHA1857, in like manner it seems that the reverend gentleman of the American Episcopal Church mentioned in the newspaper was familiar with the musical activities of the Jesuits in Shanghai, which is of course the subject of my recent book, François Ravary SJ and a Sino-European Musical Culture in Nineteenth-Century Shanghai (CSP, 2021).

Investigating further, I found out that “Mr. Styles” was actually the Rev. Edward W. Syle (1817-90), born in England, but moved to the United States where he pursued his university education (Kenyon College, 1840-43) and attended theology school (Virginia Theological Seminary, 1844). Syle and his wife went out on the China mission in November 1845. Syle had the honor of laying the cornerstone of Holy Trinity Church in 1848. He was certainly on good terms with the Roman Catholic clergy in Shanghai, and mentions in his journal a visit to the newly-completed ‘Tungkadoo’ (dongjiadu, the Cathedral Church of St. Francis Xavier) in June 1856, and a long conversation he had with Mathurin Lemaître SJ (1816-63), “a Frenchman whom I had met here ten years since”. Syle does not, however, seem to have attended the inauguration of SHA1857 on 15 August 1857, a great pity for The Project!

Eventually, Syle grew disenchanted with what he saw as a disorganized and visionless mission endeavor, and returned to the US briefly on furlough in the mid-1850s, and then again in 1862, where he involved himself with improving the notoriously bad working and living conditions of Chinese immigrants. He returned to Shanghai in 1868, and then in 1874 was appointed US Consular Chaplain at Yokohama, as well as Professor of Ethics and History at the Imperial University in Tokyo. He ultimately returned to England in 1885, his first and final home, where he was affiliated with the ECMS until his death. It also turns out that Syle was the person responsible for the purchase of SHA1865 (ex-SHA1883b), the Knauff organ at the Church of Our Savior in Hongkou, Shanghai, and no doubt the Philadelphia builder was chosen because of Syle’s American connections.

Syle was very musical, and confronted the problems missionaries invariably had in deciding on the best approach to inculturating Western religious music in a non-Western context. The is not space here to describe this in detail, so I will let him do it himself (Eurocentric values typical of the nineteenth century and all) in a letter written at exactly the same time that Ravary and Deleuze were building SHA1857. It is not too much of a leap of imagination to think that Syle was one of the many visitors to Zikawei in 1856/57, who went out from Shanghai just to see the bamboo organ destined for Dongjiadu under construction.

“Shanghai, 26 September 1856

“The Bishop has devolved on me temporarily the office of organist [at the Church of Our Savior, Hongkou] on Sunday mornings, and, as a consequence, instructing the scholars and our poor communicants to chant the few canticles which have been prepared for our chapel service has occupied me a good deal of late. They take to it with tolerable readiness, but are prone to imitate the drawling manner [sliding between tones] of cantillation that prevails among the Buddhists.

“This whole subject of music as connected with Chinese hymnology is one that has begun to exercise the minds of several among the missionaries both here and at the other posts; and by the same token it may be known, that there are a few renewed souls at every station who are asking to be taught some suitable manner in which to sing the praises of the God whom they have learned to know and love. Of course, there are three methods of meeting this want: (1st) to write hymns adapted to Chinese tunes, or (2d) to teach our own tunes, or (3d) to find out some musical tertium quid — a modification of either, or a combination of both methods.

“As far as my own attempts have gone in pursuing the first method, I have not succeeded in finding any Chinese music which, either in itself or its associations, could be profitably used in the worship. I have found one or two strains, in Chinese war songs and Buddhist hymns, which would furnish the groundwork. It chants somewhat in the Gregorian manner, and I have adopted a very peculiar air to words conveying moral instruction, such as school children might learn with interest (as indeed they do); but I have not met, nor do I expect to meet, with anything that will come up to the requirement of Christian psalmody. The whole style, conception, and manner of the Chinese music is artificial, strained, and ineffective; the notation imperfect, and the whole subject of harmony ignored.

“The second method, that of teaching and using our tunes, has been tried in many places, and with most success. As to notation, some have attempted, by reversing the order – that is, reading from right to left –to make the use of our staff and our musical notes easier of acquisition, while others have taught our music just as it stands; for which method there are so many good reasons, that I have settled down upon it myself, after having made trial of every other reasonable plan I could hear of or could invent. I have taught with the five-line staff, and with a three-line staff, and with no staff at all, but using equal squares for the beats of a measure, and numbers, to indicate the intervals [pitches?] of the scale.[1] This lost plan is not without its advantages, but the drawbacks are the same as those connected with the employment of a new alphabet, which, though it may be more perfect and more philosophical than the one discarded, cuts off the learner from every access to all that the wisdom of past ages has lodged in that older form.

“My conclusion is, therefore, that to teach our music just as we have it is the best thing for us to do; leaving it for the future Christian poets and musicians of China to work out, if desirable, that tertium quid before referred to. At present we are cultivating chanting almost exclusively; the Venite, Gloria Patri, and Gloria in Excelsis may be heard at our chapel service in a manner which would remind a stranger of the Christendom from which he is so far distant…”

For much more on Syle, the impressive work of Australian scholar Ian Welch should be consulted: https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/11074?mode=full

[1] i.e., somewhat similar to present-day jianpu notation. This numerical system had, however, just been invented in Paris about 1844 (based on earlier numerical systems, including one by J.J. Rousseau) by Émile-Joseph-Maurice Chevé (1804 –1864). It is possible that Syle learned of the Chevé system from the French Jesuits in Shanghai.

The Pipe Organ in China Project Website: Updates for May 2022

31 May 2022

The webmaster for The Project has begun upgrading various aspects of The Pipe Organ in China Project website. Visitors and users will find it much faster to use, now that the WordPress software has been upgraded to a newer version than that used in the original set-up four years ago. There are still some things in progress, and further improvements will be introduced this summer.